Sara Ahmed: ‘If addressing racism gets in the way of someone else’s happiness, then so be it’

Sana Ali talks to the self-proclaimed ‘feminist killjoy’ on how race and gender impact on our experiences within academic institutions

Sara Ahmed’s reputation as the resident ‘feminist killjoy’ and all-round incredible queer theorist is oddly cemented by her deep love for her little cockapoo. “Poppy is coming to the interview too!” she exclaims, sitting down on the floor to stroke, coo over and generally devote all her love and attention to the most sweet and well-mannered dog I’ve ever had the pleasure to meet. “Isn’t she lovely?” she asks, as we proceed to have a full-on conversation about why Poppy is the most incredible dog, and feminist theorist, to ever grace our planet.

With Poppy contently playing with her chew toy on the floor, the conversation eventually turns to more serious matters. Ahmed has held a number of different positions throughout her life. She’s worked outside the academy and within it, in roles as a professor, a guest lecturer here at Cambridge, and various senior management positions. She talks about her growing responsibilities in these academic spaces, sharpening her awareness and experience of “how the institution works in problematic ways, with the reproduction and justification of whiteness as just a part of the geography of the place.”

Want to get involved with Varsity interviews?

Meet some of Cambridge's most interesting figures and ask your burning questions. Just join our Interviews Writers group or email our Interviews team to express interest.

When probed more on this, she talks openly about the resistance the university has to actually being transformed. “The work that tends to get further is the work that requires those who have the most power to give up the least.” For Ahmed, this means the academy is often actively trying to stop change from happening, as institutions such as Cambridge “paint a profitable illusion of themselves as lively, dynamic and responsive,” whilst in reality they’re actively invested in things not changing.

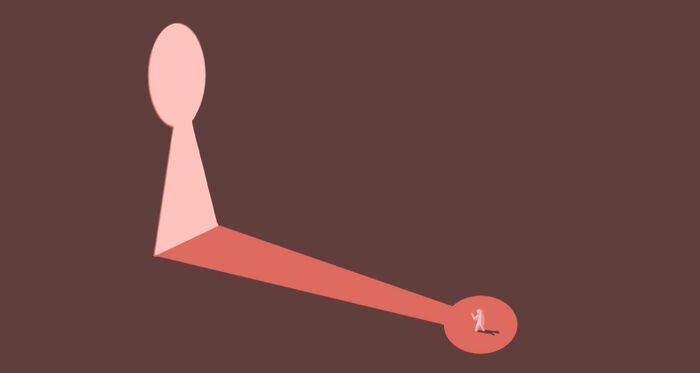

It is clear that Ahmed’s words come not only from her own research, but also from direct experience of outright dismissal and exhaustion when trying to create change from inside the academy herself. As a woman of colour, she talks about embodying the idea of ‘diversity’ simply because her body is seen as Other – as minorities are often “required to smile as part of their political duty.” Picture those happy, diverse, colourful faces on the front of corporate brochures. This image of happiness allows difficult structural inequalities and racism embedded within institutions to be concealed behind the electric buzz of ‘diversity.’

“If you think that asking questions about what and how to teach is vandalising, then just know that we’re willing to be vandals”

What Ahmed is alluding to is the idea that institutions like Cambridge neutralise and dissipate political struggles to avoid doing the real work necessary to make change happen. When asked about this in relation to the recent decolonisation movements, Ahmed refers to ‘decolonising’ itself as becoming a buzzword across the country like that of ‘diversity’, as “certain kinds of work are more acceptable and doable within the institution than others.” She emphasises the importance of recognising that even when one might consider themselves to be ‘anti-institution,’ you can never escape the potentiality of the work that you do to be neutralised, and for you yourself to be co-opted into the structures you’re critiquing.

The direct influence of black feminist thinkers like Audre Lorde is strikingly apparent in Ahmed’s work. So when asked about where she thinks Lorde’s famous quote, ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,’ fits into this paradox, Ahmed admits that “sometimes to work on the University, you have to withdraw your labour from it.” However, “more often than not it’s a case of working with it to make meaningful transformations.” Adding a few texts to a subject’s curriculum can be done, she emphasises, at the expense of some other kind of political work that requires more people to give up their power.

Despite this, she goes on to praise the ways Cambridge’s decolonise movements are based on “genuine collaborations between students and teachers,” questioning what it means to even think about our subjects and challenge them. To do this is to open up avenues for difficult conversations to be had, and work towards challenging and changing the academy from the inside. “However the institution responds, these conversations are openings and things happen in them.”

“I know the ‘feminist killjoy’, and I have always known her. She has an existence for me that she also has for others, as a difficult being”

Cambridge students, particularly students of colour, pushing for a ‘decolonisation’ movement which critically deals with the histories of colonialism and imperialism inherently tied to the University are, to use Ahmed’s own term, “vandals” in and of themselves. “Questioning dominant modes of power, even something as small as asking ‘what counts as literature?’ is understood as vandalism, the wilful destruction of the beautiful. But if you think that asking questions about what and how to teach is vandalising, then just know that we’re willing to be vandals.”

The compelling way in which Ahmed uses metaphors to describe structural inequalities evidently strikes a chord with people, from the “vandal”, to, most famously, the ‘feminist killjoy’. The figure of the ‘feminist killjoy’ takes a fundamental role in everything Ahmed does; wilful in her disruption of problematic narratives and taking up space unapologetically. “I wanted to take her up,” Ahmed demonstrates, raising her hands, “to take that common stereotype of feminists and allow it to do a different kind of work.” When asked what it is about the ‘killjoy’ that resonates so much with people, Ahmed smiles. “I know the ‘feminist killjoy’, and I have always known her. She has an existence for me that she also has for others, as a difficult being.” To then charge that figure with something “other than negation,” is to give it a vitality and energy “that you can almost communicate through” to the point where you can feel the buzz of electricity around her.

As a working class woman of colour, Ahmed’s words here not only resonate with me but hold a hopeful vulnerability that I latch onto. I imagine all the times I was that ‘killjoy’: at the dinner table, at school, at the boy spitting slurs at me from across the park. “The figure of the ‘feminist killjoy’ recognises that painful experience and says ‘yes’ to that – if addressing racism gets in the way of someone else’s happiness, then so be it.” To turn those memories of grief into something that energises is not only powerful, but as Ahmed so clearly articulates, necessary for healing.

The conversation eventually turns to the simple act of existence, as Ahmed admits that despite not spending much time teaching in Cambridge, her first thoughts about the discomfort of institutions ironically came from being a visiting Gender Studies Professor here. She describes the institution as an “old garment,” acquiring the shape of those who tend to wear it, such that it is easier to wear if you have that shape. “When you are a body for whom an institution fits, it’s seamless.” For those of whom it doesn’t fit, it is deeply uncomfortable. When Ahmed speaks of this discomfort, I think of the BME, working class, disabled, LGBTQ+ and other minority students for whom this is part and parcel of the Cambridge experience – from the discomfort of walking into a room to simply being in a place that reflects back a history you can’t be part of. “Like being a square pig in a round hole, it just doesn’t fit.”

So what, if anything, do you do with that feeling? Sometimes, Ahmed admits, “just being in the institution and getting by is enough.” She advises against creating political obligations around figures such as the ‘killjoy’. “We’re not all in that position of challenging, and that’s okay.”

However, Ahmed also recognises that for a lot of people, finding others for whom the institution is a difficult space is not only helpful but energising – “it’s hard to find those people without ending up being one of the challengers!” she laughs. Simply in sharing experiences, you’re finding a vocabulary to make sense of your experiences and what’s going on around you. It’s all about the process and “where you end up,” she continues; the process of complaining, being dismissed, finding out how things work and connecting with others who are just as angry as you is transformative in and of itself, in order to finally say ‘it’s not just about me, it’s about a system and a structure’”

“And if those structures don’t enable me to be in a comfortable way, there’s a point and purpose to challenging them.”

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Science / ‘Women just get it more’: autoimmunity and the gender bias in research19 December 2025

Science / ‘Women just get it more’: autoimmunity and the gender bias in research19 December 2025