A FLY Girl’s Guide to University: “Giving women of colour something to read that better reflects their world”

Four Cambridge-educated co-authors speak to Daniella Adeluwoye about their upcoming book A FLY Girl’s Guide to University

Lola Olufemi, Odelia Younge, Waithera Sebatindira and Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan are all recent graduates of the University of Cambridge. As women of colour studying at this institution, they often found themselves misunderstood and alone in an almost uniformly white environment. It was the tight-knit community within FLY, a network specifically by and for women and non-binary people of colour at Cambridge, that extended its hand to them as freshers. It was there that they realised that the ‘Cambridge experience’ did not have to be synonymous with being middle-class, white, cisgendered or an able-bodied man.

Now, as graduates, they are determined to make their voices and experiences heard and graciously extend their hands to you in the form of their upcoming book.

In A Fly Girl’s Guide to University, Olufemi, Younge, Sebatindira and Manzoor-Khan have created a collection of memoirs, essays, poetry and prose to help women of colour sail the gloomy sea of studying — and existing — while being a woman of colour. It puts into words the intangible feelings we walk around with as women of colour in Cambridge and comforts the reader by sharing their experiences, helping to validate others feeling the same as they did as students here.

At what point, then, did they realise that their experiences were missing from the narrative? Suhaiymah responds that “it’s not that our experiences are missing so much as they aren’t archived.”

Odelia continues: “People of colour have been using narratives and storytelling to preserve our histories for centuries.” Through this book, she remarks, “we are carrying on that tradition and giving women of colour something to pick up and read that better reflects their world.”

“I wish that, when I had been nineteen years old and going into university, those early experiences of being hypervisible as a Muslim and student of colour had not left me feeling so isolated and alone,” says Suhaiymah.

“FLY was founded before the four of us even got to Cambridge and women of colour have studied here for decades now – this book simply nods to that history.”

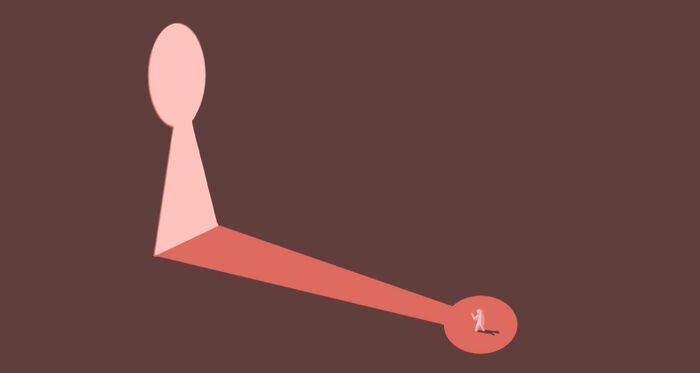

Invisibility and visibility seem a paradoxical way to describe the experiences of women of colour at Cambridge, yet they best encapsulate our experience. Feeling unanchored from the things that make everyone else feel comfortable in their identities makes us feel hyper-visible. Yet this sense of hypervisibility is contrasted by a feeling of invisibility when we encounter microaggressions. She continues by stating that this book “will hopefully validate others feeling the same and place them in part of a wider struggle, [shifting] the focus from them as individuals to a wider system that makes them problematic when they are not the problem.”

For Suhaiymah, the motivation behind the book is simple. “The marginality of women of colour in institutions like Cambridge is not just physical and social but intellectual too; our experiences, labour and resistance efforts are rarely noted or recorded so in that sense this book is aiming to counter that erasure which is not solely a lack, but a political void. FLY was founded before the four of us even got to Cambridge and women of colour have studied here for decades now – this book simply nods to that history.”

I ask them about the process of writing the book. Did it arouse a sense of vulnerability or was it a rather liberating feeling? For Waithera, the hidden space of FLY within the hyper-visible ivy clad structures of Cambridge allowed her to make her experience visible during her time here. “By the time it came to writing, it felt liberating to be using these stories to try and effect whatever meaningful change will hopefully be brought about by them.”

Suhaiymah points out that vulnerability and liberation do not have to be opposing feelings. For her, “to write your truth will always be both terrifying and liberating, I don’t think you can have one without the other.”

She mentions how she always goes back to what Audre Lorde said about writing: that “we write to survive, that writing is the act of defining and speaking for ourselves in a world which so often wants to speak on our behalf and define us in constraints made by society and history.”

“I wrote with the assurance that someone somewhere feels the same”

“It is also easier to write when you know you’re in good company and that your words don’t stand alone - I wrote with the assurance that someone somewhere feels the same, and that the women writing with me would speak in validation, not opposition, that confidence itself made the writing a freeing experience.” Writing can certainly be an important process for it is within writing that we form ourselves. Through words we are able to explore ourselves – as words flow from the tip of the pen about to be birthed, they are already felt.

The publication of A FLY Girl’s Guide to University is a testament to the increased visibility of women of colour both in our University and the wider world. But, I ask, what has not been addressed and what progress still needs to occur? Odelia responds that visibility is important but it is systems which have made us invisible. “Visibility sometimes makes us forget what is still greatly unseen and believe that progress has occurred when problems get repackaged through new oppressive structures and systems.”

When I ask them how this can be addressed, their answers are all different, indicative of their unique experiences. “We need the oppressive structures to be broken down, and we need to replace them with spaces that nurture women of colour.”

“Diversity must include inclusion and that inclusion must be radical and aimed at disrupting the current, restrictive systems that have yet to even fully reckon with the lack of engagement with people who look like us in the curriculum,” says Odeila.

For Suhaiymah, visibility is not the end goal. She discusses how she became more aware of her visibility as a hijab-wearing Muslim woman of colour under the University’s duty to act according to counter-terrorist legislation Prevent. When people complain that free speech, a ‘fundamental British value’, has come under threat on university campuses because of safe spaces, there seems to be a general silence on the fact that Prevent limits the literature that students can access and the topics about which they and their educators feel they can speak and write.

The four co-authors are excitingly busy with the release of their book around the corner, so I have one final question, this time for Lola Olufemi. How can current students become comfortable with being critical and angry towards institutions that weren’t made for them and still feel grateful that they’re at one of the best universities in the world?

“One way to be grateful is to constantly resist the idea that there is something unique or special about us... Being grateful does not mean being apolitical or in awe of the institution. It means challenging it, sabotaging it where necessary, redistributing resources. When you do that with other people and work collectively, then you can understand the power that students have over what we learn and how we learn it.”

A Fly Girl’s Guide to University is out on 24th January and it will have its first book launch in Cambridge on 26th January in Trinity Hall.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025

News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025