Universities’ finances cannot rely on soaring rents

Ben Beach urges university managers to take action against the pressures generated by the rising cost of student accommodation and tuition fees

As part of austerity measures designed to marketise education, the 2010 trebling of tuition fees brought with it huge reductions in central government funding. Undeterred by fierce resistance from students and education workers alike, university managers – principally through the Russell Group – lobbied extensively in support of the fee increase; despite the prospect of steep funding cuts being planned for as early as 2009.

This seemingly contradictory approach can be reconciled if understood as a process of financialisation: unlike public sector funding, the private nature of individualised student fees enables their use to securitise debt, in turn financing capital investment, which is a key objective of the Russell Group. Put simply: your fees are being leveraged to fund previously impossible expansion programmes, with returns supplanting lost government funding.

Maximising revenues from university estates – principally in the form of rents – is central to this strategy. Consequently, universities are undertaking massive urban investment programs in lucrative sectors such as student accommodation; frequently with questionable academic benefits and the exacerbation of gentrification issues. The Financial Times reports that in 2016, $1.39 Billion of UK higher education bonds – secured on fees – were sold to global investors, funding projects such as UCL’s new Stratford Campus. Threatening over 700 social housing tenants with eviction, UCL’s ‘campus’ is predominantly private housing, student halls and commercial rental units with negligible academic space.

“Data from Jesus College suggests just 8 undergraduate rooms would meet Shelter’s test of affordability”

Universities as diverse as Cardiff, Sheffield, Strathclyde and Southampton are now borrowing heavily to invest in rent-yielding accommodation blocks, with UAL currently facing severe criticism for displacing communities in south London. Cambridge is no exception, with the estate management strategy explicitly designed to improve the University’s financial position. Owing to the billion-pound North West Cambridge project, the University is now the largest property developer in the region, constructing thousands of homes either for rent or market sale. The University claims the North West Cambridge development will provide “affordable accommodation”, yet a room at Swirles Court is £6,080 – 72 per cent of a maintenance loan.

Shelter, the housing charity, calculates a genuinely ‘affordable’ rent as under 35 per cent of income, equating to £2,950 of a maintenance loan. But the majority of college accommodation is significantly more expensive, leaving many students paying much more than they can afford. Data from Jesus College suggests just 8 undergraduate rooms would meet Shelter’s test of affordability, while at Murray Edwards first-years are exclusively offered rooms priced at £1,825 a term. If recent criticism over social exclusion has not alerted Cambridge to the obvious barriers high rents present, the University itself estimates living costs for 2018-19 at £9,160. The maximum maintenance loan available to low-income students is £8,430.

High rents are essential to financing the post-2010 marketisation of universities and across the country, and the impact on student welfare has been disastrous. A recent NUS survey found over 50% of respondents could not afford rent and basic expenses, fuelling an escalating mental health crisis and even growing food bank use. Amongst Cantabs, the Big Cambridge Survey has demonstrated widespread disaffection with maintenance issues and accommodation costs, with an astounding 77 per cent of residents at one college – Newnham – voicing grievances over pricing and quality. Stories of hardship are tragically common, recently illustrated by a student informing the Cambridge Cut the Rent campaign that they had been forced to discontinue their studies. We cannot afford this situation to continue.

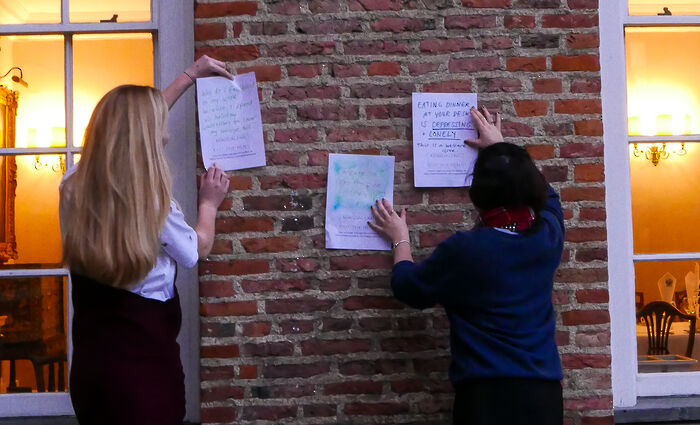

However, universities’ dependence on rental income presents an Achilles’ heel for managers and a vital pressure point for students, who through collective organising are exacting major improvements. After tiring of having petitions and protests ignored, last year over 1,000 UCL students took part in a series of escalating rent strikes, winning over £1.5 million in rent cuts and bursaries for low-income students. Similar tactics at SOAS and Goldsmiths led to over £650,000 in compensation, while in December, merely threatening a rent strike yielded students in one Sussex hall £64,000 in just four days.

With institutions increasingly debt-burdened, any significant interruption to revenue streams is a serious concern for managers, who thanks to public image concerns are heavily constrained in their options for enforcement. As Cut the Rent groups continue to spread across Cambridge, over 500 students have signed up to growing calls to take action. High rents are exclusionary, socially damaging and integral to the market-orientated model of the neoliberal university. But as a private issue becomes a collective conversation, the pressure for change is rising. Rent is everyone’s problem: university managers will ignore it at their peril

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025