Our studies should amount to more than the grade we achieve in exams

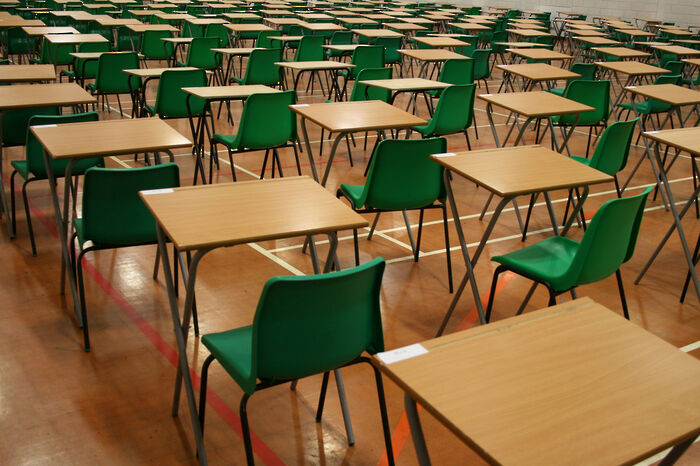

With exam season looming, Madeleine Wakeman questions the efficacy of examinations as a mode of assessing students’ abilities

Examinations are engrained into our lives. From as young as 11 we are examined and assessed, and our worth depicted by letters or numbers on a piece of paper. But modern exams are no more than a memory test. Students are tested on how much they can cram into their mind and spill out on paper, rather than on the depth of their understanding. Despite spending at least a year learning meticulous details, students are only given a few hours to represent their understanding of an entire module.

Students conceptualise exams, not as a method of testing their knowledge, but as a ‘game’. One learns to ‘play the examination game’, rather than fully learning and understanding concepts. Students try and predict the few topics that will come up, memorising a few token pieces of information to give the examiner the impression that they have a well-rounded knowledge of the subject at hand. In this sense, exams are neither an effective nor accurate representation of work ethic, understanding, or ability. So what are exams actually trying to achieve?

Exams are neither an effective nor accurate representation of work ethic, understanding, or ability

The reality is that life, and work, is not a memory game. A lawyer will not regurgitate a list of cases during a cross-examination, but will take time over the matter, researching cases and relevant authorities prior to a trial to provide accurate advice applicable to the client’s individual circumstances. Equally, a doctor won’t rashly guess the medicine to prescribe to their patient without first double checking it against a database.

How could students be assessed better? One option, rather than having exams at the end of the year, would be to assess students throughout the year. Students could regularly hand in essays, completed over the course of a week and with access to all their materials and resources, and universities could employ the same safeguards used to prevent plagiarism that are used for PhDs and dissertations. This would abolish assessments of how much of the textbook a student has memorised, but rather assess how students critically analyse and explore the information, using it to build upon their own arguments.

Ending exams might reduce the disparity between able-bodied students and those with learning difficulties

But would this approach just serve to increase the pressure on students? While it would mean that students are assessed more frequently, it might actually reduce the disparity between able-bodied students and those with learning difficulties, such as Dyslexia or Dyspraxia, who may need more time to understand and engage with concepts. I suffer from Dyspraxia, which means that I have a weak working memory. If exams were to test my ability to assess critically and analyse the information I am provided with, rather than my memory, my results would be much more reflective of my true ability.

Another option would be to have no exams at all. Think about it: exams produce a grade which allows employers to rank students, supposedly according to intelligence and academic ability. After all, for most employers, a grade isn’t even enough – they typically will ask for require an interview, attendance at various assessment days, and evidence of numerous work placements.

Ultimately, university should be about more than achieving a particular grade. Exams encourage students to view their studies as a means to an end, rather than an end in themselves. Without exams, students could explore the areas of their degree which interest them, read further where they desire and develop a genuine passion for their subject. In this sense, exams are truly not worth the paper they are printed on.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025