Middle class students must attend to our own privilege when charity shopping

Second-hand clothes shopping isn’t as ethical as it could be, argues Isobel Duxfield

The second-hand clothing industry is undergoing a paradigm shift. Once a sign of low economic status, used apparel is now en vogue; from London to San Francisco, the urban elite are ditching designer labels for castoff Nike and soiled Adidas.

For many, this trend is cause for celebration, and resale has been welcomed as the antidote to fast fashion’s environmental devastation and human rights abuses. However, as the second-hand sector seeks to capitalise on its commercial success, it is beginning to alienate the very communities it initially intended to serve.

Used clothing is big business. Since the 1990’s the industry has ballooned, worth a staggering $24 billion in the U.S. alone. With the sector predicted to hit $64 billion within the decade, apparel resale is snapping at the heels of major retailers. With Zara’s meagre profits and Forever 21’s collapse into administration linked to a new rejection of fast-fashion, large corporations are understandably getting worried. From flea markets to apps (like Depop, Vinted and even eBay), thanks to new technologies, the pressure for sustainable practices, and a global financial crash, it is getting increasingly easier to welcome sustainable fashion with open arms.

A sustainable alternative to today’s fast fashion is undoubtedly needed, and quickly

Indeed, a study by Thredup noted a 25% rise in second hand clothing purchases between 2016 and 2017 alone. Sites like eBay and Depop peddle affordable second-hand apparel at the push of a button and have proved immensely popular. 71 million users list 20 million items on eBay everyday, while Depop has raised over $100 million from the sale of over $500 million worth of goods by its members. Used clothing is officially trendy - and profitable.

This circular economy has been touted as a sustainable solution to current consumption patterns of ‘fast fashion’. Eighty billion items of clothing (most of which end their lives at landfill) are purchased each year, a 400% rise on a decade ago. Considering outlets like Primark flog garments for as low as £1, wasteful behaviour isn’t surprising. As demand rockets and unit prices plummet, multinational corporations ship garments across the globe, leaving a trail of devastation in their wake.

Used clothing resale may appear a beneficial alternative, but it isn’t a solution. Responsibility is placed on consumer shoulders, ignoring the immense environmental damage caused by apparel multinationals. This process is enabled by unparalleled human rights abuses. Devastatingly low wages and horrific working conditions are endemic across supply chains, with the global south - particularly women - falling victim to fast fashion’s ceaseless production of cheap attire.

H&M is a prime example. In 2015 and 2017 violent protests against pay and working conditions erupted in their Myanmar factories, yet despite trumpeting improved conditions through their ’Roadmap to a Fair Living Wage’, H&M’s business model remains wedded to exploitative practices. A few pennies added to the pay packet is simply a PR exercise.

At the opposite end of the scale, as the second-hand market expands, used garments come at a premium. Even charity shops are upping their prices. Since the first charity shops opened their doors in the late 19th century, stores have provided low-cost but high-quality necessities for low income groups. However, piles of £2 t-shirts are a thing of the past and the second-hand store is now a far more commercial endeavour.

Indeed, analyses of contemporary clientele reveal that the average customer is not from the lowest tax bracket. Those who rely on second-hand to clothe themselves are increasingly finding themselves priced out as demand for shabby-chic drives prices skywards.

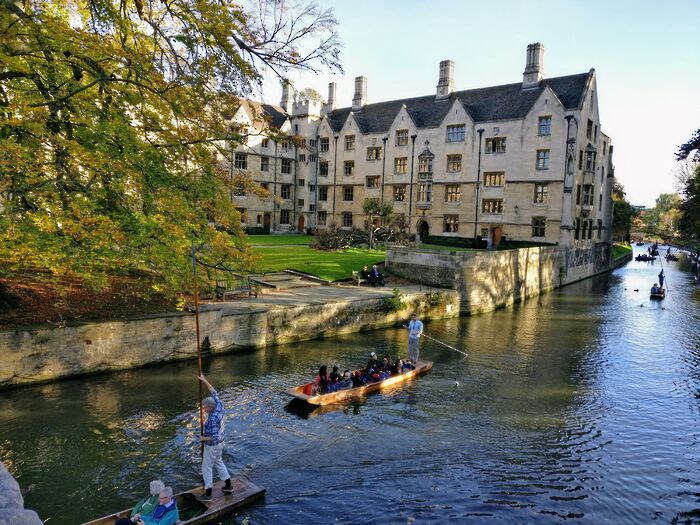

The Charity Retail Association is quick to defend business practices, noting that the average sale is still only around £5. However, this obscures a concerning trend: organisations such as Oxfam and Shelter are pouring increasing resources into capturing bourgeois footfall by opening ’boutique’ stores, managed by qualified staff, in gentrified quarters of London, Cambridge and Oxford. Wander around exclusive districts like London’s Marylebone and St. John’s Wood and you will find local charity shops flogging Karen Millen coats and Jimmy Choo’s at prices one would not consider a bargain.

Rising price tags come at a cost. Such commercialisation may be netting charities vital funding, but many allege that charity shops are no longer serving vulnerable communities. You may consider your NorthFace puffer jacket to be a bargain at £30, but this is far beyond the means of many who once turned to the thrift store for their winter coat.

A sustainable alternative to today’s fast fashion is undoubtedly needed, and quickly. As the planet burns and textile workers starve, H&M’s days of churning out mountains of expendable attire are numbered. Buying recycled and reused garments presents an ecological and affordable solution, particularly for students. However, we must attend to our own privilege when shopping for a second-hand bargain: is our fervour for vintage marginalising individuals less fortunate than us?

This will also be a pertinent question for charity shops in the coming years, as they seek to navigate the line between financial security and localised social responsibility. However, this cannot be an excuse to abandon campaigns for reform to the fashion industry. With Black Friday just around the corner, it is gratifying that 300 brands are urging their consumers not to partake, but it is not enough. We need to consider the ethics of both fast fashion and sustainable fashion year round.

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025 Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025

Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025 News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025

News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025