On cancelling cancel culture

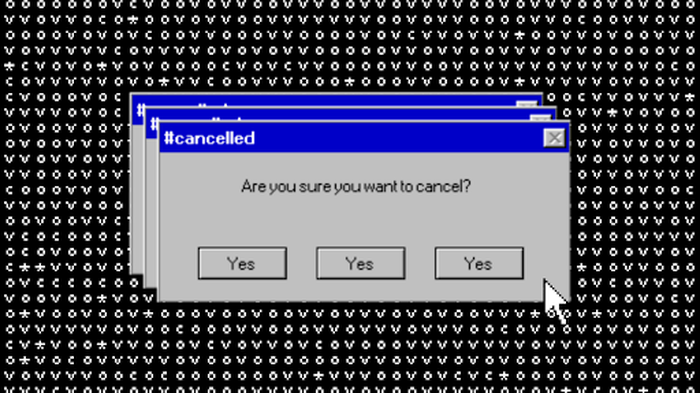

An anonymous student criticises the court of public opinion and stifling of debate that cancel culture has encouraged in recent years.

I can still remember the first time I heard about the phenomenon of ‘being cancelled’: it was just earlier this year, when my friend said, in a rather amused fashion, that so-and-so was cancelled. If I’m honest, I can’t remember who, as at this point I have lost count.

Just in case you have been living under a rock for the past year, cancelling involves a boycott of support for a celebrity or company that says or does something considered offensive. It does not matter whether the intention behind such actions was malicious or not. It is generally followed by public backlash and the premature ending of careers/profit – if not the literal end, then the permanent marring thereof. A quick scan of the internet reveals a whole score of celebrities who have been cancelled for a host of reasons. It looks as though attempts have been made to cancel nearly every major celebrity that has ever existed: Ariana Grande, Demi Lovato and Taylor Swift have all been targeted.

Not many cancellation attempts have been wholly successful, as many of these accusations are eventually rendered futile. However, just because celebrities can make comebacks does not mean that they mentally recover from the situation overnight. Receiving a torrent of hatred online is not easy for anybody, especially if it is completely undeserved. It is important to remember that when we make comments online, they can and do cause great upset; even celebrities are not immune from human emotions.

We must also think more carefully about the type of online community we want to foster. If we spend half our time cancelling people who we think are truly terrible, then we create a community of resentment, hostility and division. Even if someone is worthy of disapproval, we can do better than hurl generalising insults their way.

“Cancel culture is...rife with holier-than-thou attitudes.”

Despite this, cancel culture has ensured that prominent figures lose their position of authority in cases of genuinely reprehensible behaviour. Harvey Weinstein is an obvious example of this, prosecuted thanks to the hard work and dedication of the #MeToo movement. Likewise, few people were sad to see the removal of Katie Hopkins from Twitter. Her unrelenting capacity to hate and ridicule is something that should not be encouraged, and Twitter has become a more loving place in her absence. As well as holding people accountable for their actions, cancel culture has given a voice to historically marginalised communities where most other movements have failed. For all its criticisms, there is a lot to be said in cancel culture’s favour.

However, cancel culture isn’t exactly known for giving people fair hearings. If, for whatever reason, the media starts a campaign against you, you don’t really stand a chance. People’s views are malleable and often easily shaped by mainstream media; once an opinion becomes popular, it becomes more stubborn and less tolerant. People who never thought about having an opinion on you before now feel very strongly that they hate you, and always will. Once mainstream opinion is against you, you’re in quite a difficult spot. Anything you say could incriminate you even more. And even if you say something legitimate and logical, the media have no obligation to publish it.

A recent public letter condemning cancel culture, signed by the likes of Noam Chomsky and Margaret Atwood, argues: ‘professors are investigated for quoting works of literature in class’ and ‘[researchers are] fired for circulating a peer-reviewed academic study’. In other words: we all have the potential to do or say something offensive, whoever we are, without even knowing it is potentially malicious to begin with.

In a way, cancel culture could be considered a form of utilitarian democracy. Someone behaves in an unacceptable way, and then the public vote with their feet by voicing their opinions on person X, unfollowing X, and refusing to buy their products anymore, be they commodities or performances. Then corporations stop endorsing person X, X is slashed from the new film, or X is no longer the face of the company. Public denunciations are made, and the verdict is passed: guilty.

“By deciding that there is one objectivity, i.e. that someone is cancelled because they deserve it, debate is put to a stop.”

My problem with cancel culture, though, is simple: it does not provide enough room for conversation and debate. Once it has been decided that you are in the wrong, anyone who tries to stand up for you is also in the wrong. You are correct if you agree with cancel culture, and fatally mistaken if you dare to disagree. There isn’t room for conversation when cancellers are not willing to engage in it. Moreover, if you defy the odds and try to create such conversations, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Cancel culture is thus rife with holier-than-thou attitudes. It provides anyone with the opportunity of being on the right side of history by joining the woke masses. Membership is free, no questions are asked, and nothing is expected of you except that you agree with whatever is said.

Naturally, many people relish this opportunity. They can preach all they like, knowing they are indisputably Right, and sigh at those ‘less Enlightened’ who do not understand what it’s like to be correct about everything. Take a recent Guardian article cancelling the word ‘flattering’ for being akin to ‘passive-aggressive body-policing’, and a ‘euphemism for fat-shaming’. It sometimes feels as though people are just picking fights that don’t need to be fought and finding new perpetrators of heinous crimes by the minute (in this case, most of the teenage population for innocently complimenting their friends).

I worry that cancel culture has become overzealous in its mission to be right about everything. By deciding that there is one objectivity, i.e. that someone is cancelled because they deserve it, debate is put to a stop. People are frightened to speak out because the consequences could be both socially and professionally dire. To be clear, I am not referring to people who are frightened to speak out and say something atrocious in support of despicable crimes. Instead, I am referring to those who say that it is okay to disagree with the conclusions of cancel culture. People should be able to do this without risk of being ‘cancelled’ themselves.

To be completely frank, I am frightened. I am frightened that cancel culture has gone too far: that it is encouraging an authoritarian culture by silencing dissenting voices, as well as dictating what a dissenting voice even means. Nobody is exempt from cancel culture, and the consequences can be devastating. It’s high time that we at least cancel the toxicity of cancel culture, to leave only its potential for positive change behind.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025