As an autistic woman, I have been overlooked and understudied

Ella Catherall writes about being an autistic woman in Cambridge and the lack of representation of her experiences in research and the popular perception

From TV shows to books to movies, more and more autistic characters are being introduced into popular narratives. While this increased representation is good, one issue is that almost all fictional characters with autism are male. Some argue that this reflects a real-life pattern — after all, four times more men than women are diagnosed with autism. The idea that autism is a “boy’s issue”, is, however, a serious misconception: there are many women with autism.

I am one of them. When my parents told me that they thought I might be autistic, everything made sense. Suddenly, I didn’t feel so insecure about my interactions with other people, or the fact that I cried a lot in class. I now want to raise awareness of the fact that women can be autistic, too, in the hopes that this may encourage more women to embrace this part of their identity: something I have found to be a truly liberating experience.

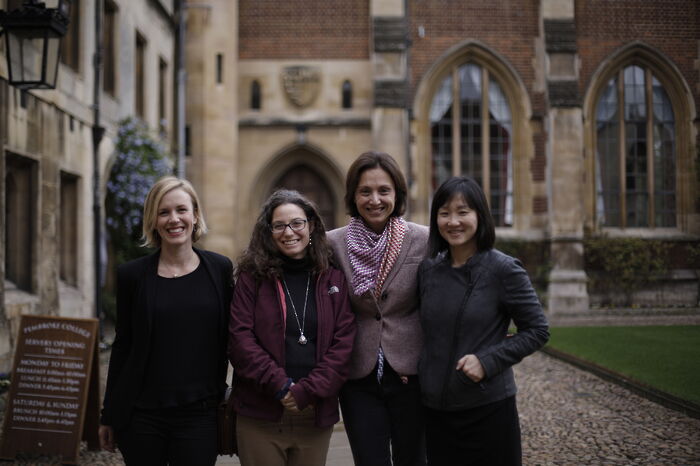

12% of Cambridge students are on the spectrum, compared to only 2 to 3% in the general population. At Cambridge, I met Maia, Lillian and Kiki — first year women students with autism. Although our stories differ, they share important features: compared to boys, we were diagnosed late — and at first, incorrectly. Kiki was initially misdiagnosed with anxiety and depression, saying that she “had to wait a long time for the right team”. Lillian is yet to be diagnosed and has only realised that she is autistic relatively recently; she is from China, where the culture surrounding autism is toxic – “it’s almost like you can’t have any social value if you have autism”. She said that the media presentation of autism is that people with the condition need to be cared for and pitied, as opposed to being understood and treated as equals. It is as if a boundary is set up between neurotypical (non-autistic people) and autistic people, leaving the latter feeling very isolated. She says that she feels that the general attitude is “You’re different. We’re not going to stop you being different but we’re not going to interact with you any more.”

"12% of Cambridge students are on the spectrum, compared to only 2 to 3% in the general population"

I wanted to find out more about the science behind autism, and came across what is known as the female autism phenotype. According to this idea, there are just as many autistic women as there are autistic men, but women present themselves in a different way to autistic men, and are therefore less likely to be diagnosed. Instead, many are misdiagnosed with conditions such as anxiety, depression or multiple personality disorder. Being autistic and female does, however, increase the chances of a person suffering from anxiety, depression and eating disorders.

Hans Ansperger, the first person to have theorised the condition in 1938 initially thought that autism was primarily a male condition. A month ago, Professor Francesca Happé from King’s College London told The Guardian that hundreds of thousands of girls and women with autism are going undiagnosed due to it being viewed as a “male condition”.According to Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Cambridge Autism Research Centre, “autistic females on average may try to hide their autism more than do autistic males, perhaps a reflection of the greater pressure on females in our society to fit in and be sociable”.

While many autistic boys, upon hitting puberty, become aggressive, girls are more likely to be anxious. In my case, that manifested by being so scared of getting a detention in school (something that never actually happened to me) that I threw up every Tuesday morning before assembly. Because the stereotypical autistic person is male, it has been difficult for researchers to recognise the ways in which autism presents itself in women. Many women have had issues when trying to persuade healthcare professionals that they are autistic. All of these factors result in it being less likely that adults in the girl’s life will notice that she is more than just a bit eccentric. Professor Baron-Cohen mentioned that as clinicians’ awareness of the female autism phenotype increases, the ratio of diagnoses is slowly moving from 4:1 men to women to 3 or 2:1, “which I think is getting much closer to the true sex ratio in autism,” he said.

"When my parents told me that they thought I might be autistic, everything made sense"

Not everything is different for autistic women, however. Socialising is an issue for all of us. Kiki described socialising as a “very high risk, high reward activity”. Statements often confuse her, and that quickly turns into paranoia, a sentiment echoed by Maia: “Sometimes if I talk to people it will go badly and I don’t know why.” The issues with socialising can have large impacts when starting at Cambridge. I, for instance, struggle to start conversations with people unless I already know that we have a shared interest. This means that for me, college group chats are a gift – having one made the transition much easier for me. Lillian said that “the toughest experience I’ve had so far is dealing with a lot of new friends – I have no idea how much time or how much effort I should put in because there’s no clear boundary. Obviously, I like to make new friends but I don’t know how much effort to put in to get them to accept me as a friend.” When asked about how her condition has affected her first month at uni, Maia said that “I had a good five days where I didn’t really have a routine that I was in, because lectures hadn’t started yet and I didn’t really know what I was doing…I felt very alone, which definitely had an impact.”

“Sometimes if I talk to people it will go badly and I don’t know why”

She also had issues with executive function, making it hard for her to organise her thoughts. After talking to the college counsellor, this was put down to the fact that she was wearing her glasses more – such a subtle change can have a massive impact on people with autism. However, the support here in Cambridge has so far been excellent. Kiki said that “this is the only university that was able to make my mum feel better about me living independently” – she has access to a counsellor, a mentor and a study skills tutor. Maia has also had great interactions with her college counsellor, who was very experienced in dealing with people with autism. For Lillian, the fact that society is more accepting of autism here is very freeing; she now feels less isolated and more like she can properly be herself.

Maia said that she cried during the movie Ghostbusters because of the (apparently unintentional) autism representation. Finding a character that you just ‘get’ can have that impact on anyone, not just autistic women, but it is rare for us. We need to stop thinking that autism is just a male condition. When it comes to autism, anyone can be affected

Comment / Cambridge is a masterclass in nostalgia11 March 2025

Comment / Cambridge is a masterclass in nostalgia11 March 2025 Lifestyle / The art of slowing down10 March 2025

Lifestyle / The art of slowing down10 March 2025 News / Caius threatened with legal action after accommodation fiasco7 March 2025

News / Caius threatened with legal action after accommodation fiasco7 March 2025 News / Cambridge spends over £9M on academic journal costs7 March 2025

News / Cambridge spends over £9M on academic journal costs7 March 2025 Arts / Contemplating Edward Hopper from Cambridge7 March 2025

Arts / Contemplating Edward Hopper from Cambridge7 March 2025