Gay blood is not dirty: Examining the science and politics around MSM blood donation

Sexually-active gay and bisexual men are disallowed from participating in some clinical trials for COVID treatments. We must “set free the spectre of pariahship cast over Britain’s LGBT+ community by the AIDS crisis”, argues Ben Hollingdale.

On Saturday, it was announced that gay and bisexual men will not be able to participate in a new clinical trial which aims to test the efficacy of convalescent plasma as potential therapy for those still suffering from COVID-19. The stipulation is consistent with NHS policy on blood donation as of 2017 but some fear it risks alienating a whole community of potential donors. In any case, this resurfaces some important questions about the reasons men who have sex with men (MSM) can’t give blood. Are there scientific grounds for excluding MSM from blood donation or is public health policy still informed by outdated tropes about gay men, promiscuity and perversion?

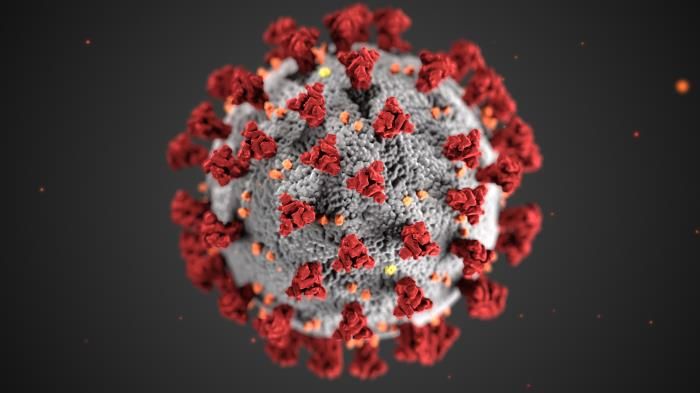

In the treatment, blood is taken from a donor who is fully recovered from the virus and has been asymptomatic for no fewer than 28 days. The plasma, the yellowish liquid component of the blood, is separated from the haematocrit, the insoluble cellular components of the blood, by a process called apheresis before being introduced into the bloodstream of a virus patient. In the trial, plasma will only be given to patients whose condition has continued to deteriorate despite being treated with existing therapies such as antiviral agents and corticosteroids. In studies from previous SARS outbreaks, convalescent plasma has proved effective as a last resort in lowering mortality rates and reducing hospital times for patients, with its success attributed by some to its ability to reduce viraemia (the density of viral particles in the blood). This is consistent with the viral load theory being presented by some outlets as the reason healthcare workers are being disproportionately impacted by the virus.

“Concerns surrounding MSM blood donation stem from the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and 90s”

But what does this have to do with gay men? Without specific reference to the sexual orientation of potential donors, the World Health Organisation (WHO) cite participation in “high-risk sexual behaviours” among their list of donor exclusion criteria. Since blood-borne infections like HIV, HBV and HCV may persist in the blood for a short period of time (known as a window period) before showing up reliably on tests, the WHO warn such donors present a higher risk of passing on transfusable-transmissible infections (TTI) to blood product recipients. Since 1980, MSM have been classified as one of such “high-risk” groups in the UK, ostensibly on assumptions that they are more likely to engage in unsafe sex practices, have multiple partners and ultimately are at increased risk of contracting and passing on certain sexually transmitted infections. Labouring under a lifetime ban on all blood donation as recently as 2011, gay and bisexual men may now give blood in the UK so long as they refrain from engaging in oral or anal sex for a minimum of three months before donating.

“So why do restrictions persist in the UK?”

It is clear from the chronology of these restrictions that the concerns surrounding MSM blood donation stem from the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and 90s. The New York Times published their first report about a common virus in homosexuals in 1981, but stigma around queer sex practices being somehow ‘dirty’ or ‘unclean’ has existed in the public imagination for much longer. For researchers, refuting that the inclusion of MSM donors would pose a significant risk to contaminating blood products with HIV/AIDS has proven difficult, principally because the data accessible from blood services is not that good. One review, published in 2015 stated that “high-quality studies investigating the risk of TTI in MSM are scarce”, describing the data as “too limited to be able to unambiguously/clearly recommend a certain deferral policy”. In the absence of robust data, mathematical models have been used to predict the effects of reducing deferral intervals for MSM on the spread of TTI, but these methods have failed to produce decisive results. In 2001, Italy lifted their lifetime ban on MSM in favour of an individual assessment of sexual behaviours during donor screening and found no evidence of a significant impact on the HIV epidemic in data collected in 2009 and 2010. Since then, other European countries like Spain have implemented similar policy changes with no significant outbreaks.

So why do restrictions persist in the UK? While the WHO acknowledges that “MSM account for the largest subpopulation of HIV-infected people in most developed countries”, it seems intuitive to most people that a man in a monogamous same-sex relationship would not present a greater risk simply by virtue of being gay than a straight man with multiple sexual partners. Speaking to ITV News, Keith Ward, whose long-term partner Andy Roberts was denied participation in the new trial, said “it only goes to show that in the UK being gay is still thought of as a form of contamination”. It is likely that financial concerns in the NHS are affecting the pursuit of a new policy on MSM blood donation, finding it more convenient to maintain existing deferral periods than to invest in more rigorous donor screening, HIV surveillance and wider research an updated policy would require.

“In many ways, the way we think about queer people now has changed for the better”

But what effects might such legislation have on the mental health of a community still fraught by an epidemic of their own over 30 years ago? Writing in 1989, American essayist Susan Sontag described those living with AIDS as “a new class of lifetime pariahs” made to feel dirty and subhuman by the effects of their illness and castigated as such by the institutions in place to help them. Stories of ‘super-spreader’ Patient Zeros, such as in the 1987 book And the band played on by Randy Shilts, told of hyper-promiscuous gay males who, ignoring “incontrovertible information” about their condition, continued to spread the disease with little regard for their own health or that of their multiple partners. These narratives littered the cultural conversation surrounding AIDS to the extent that gay and bisexual men, regardless of their own serostatus, saw themselves as agents of infection; dirty by default and damned to be so by the very virtue of their identity.

The AIDS crisis epitomised the medicalisation of queer people as a form of ‘social contagion’ as they were presented in earlier sociology and psychology. In many ways, the way we think about queer people now has changed for the better. Decades of dedicated activism have led to patent advances in LGBT+ rights, representation and acceptance. However, the hesitance to review these policies systematically in contemporary Britain coaxes queer people into thinking the way our institutions view us has changed when many of the policies surrounding us are still soiled by the legacy of an illness which devastated our community more than 3 decades ago. In lifting these restrictions, we would set free the spectre of pariahship cast over Britain’s LGBT+ community by the AIDS crisis and simultaneously allow queer people to participate in the relief of another pandemic that has already affected so many in the UK and around the world.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025