Dreaming through quarantine

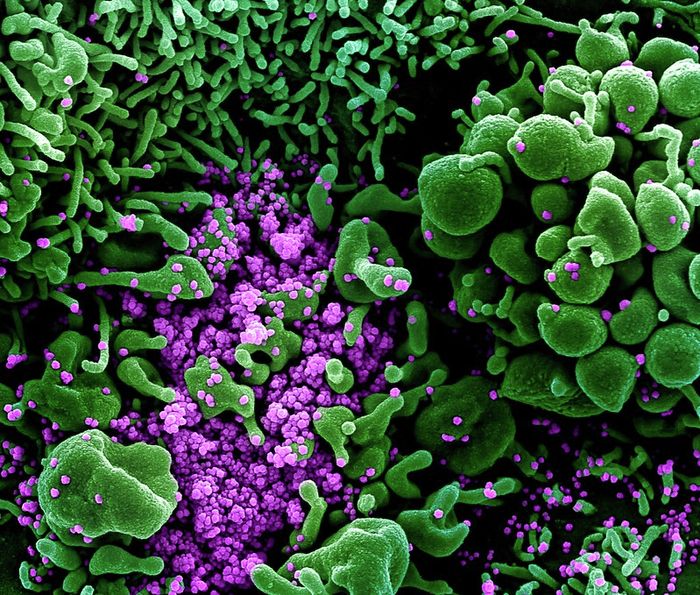

Sambhavi Sneha Kumar explores why and how we dream as well as current studies on dreaming during quarantine under COVID-19.

Whether pleasant or a nightmare, dreams are one of the murkiest areas of neuroscience. Their purpose is unclear and what determines their content and recollection remains ambiguous, though many theories and mechanisms have been proposed for the process of dreaming. Recently, our daily lives have been transformed by quarantine - it is not unreasonable that it might affect how we sleep. Many organisations such as the Italian Sleep Medicine Association are collecting data as to how sleep-wake rhythms have been affected by self isolation. Since lockdown, there have been reports of individuals experiencing more vivid dreams than before and being able to recollect them with greater accuracy. Blogs such as https://www.idreamofcovid.com/ have been created where people can report their ‘lockdown dreams’ and have gained huge traction.

“Whether dreams are remembered or not depends on a multitude of factors, many of which are linked to the sleep cycle.”

Dreaming tends to occur during the REM (rapid eye movement) phase of the sleep cycle, which only starts approximately 90 minutes after falling asleep and accounts for 20-25% of total sleep time. One of the most widely accepted theories for dream generation is the Activation Synthesis Theory, which, on a molecular level, describes how the pons (a part of the brainstem) releases the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which travels to parts of the forebrain. Activation of these regions results in the seemingly meaningless images that make up our dreams. This process can then be switched off by other neurotransmitters, noradrenaline and serotonin, which are also released by the brainstem.

REM sleep is often known as the ‘paradoxical’ phase because of its neurological similarity to the wakeful state. Neuronal activity in the forebrain appears to be similar as when awake, observed by electroencephalography, whereas in non-REM sleep forebrain neurones are less likely to fire. Furthermore, muscle tone drops to such an extent that the body is almost completely paralysed, achieved by inhibition of motor neurones. A small potential difference usually exists across the axon membrane of these neurones, and during REM sleep the membrane is hyperpolarised by around 2-10 millivolts, further away from the threshold needed to ‘fire’. This state, known as ‘REM atonia’, ensures that we do not ‘act out’ our dreams.

“Much of research that has been carried out is vulnerable to unusual data due to the effects of subjects experiencing poor sleep in a laboratory environment”

Even for people who claim that they ‘don’t dream’, evidence including this 2015 study demonstrates that dreams (mental activity whilst sleeping) take place for everyone. Whether dreams are remembered or not depends on a multitude of factors, many of which are linked to the sleep cycle. Perhaps most relevant to the current pandemic, anxiety can hugely influence dream recollection. If awoken during the REM phase, an estimated 80% of neurotypical people will be able to give a relatively detailed account of the dream that they were experiencing. It has been suggested that anxiety can lead to poorer sleep quality, including increased waking during the REM phase. Data from Italy demonstrated that although those in isolation reported spending more time in bed, they experienced a lower sleep quality than before, though research is still in its early phases. With workers worrying about pay, students stressing about exams, and loved ones at risk on the frontline it is no wonder that during this pandemic anxiety is on the rise, even in those who have not been infected themselves. This could possibly be leading to increased waking throughout the night, and better dream recollection as a result.

In terms of content, it is widely acknowledged that dream experiences can be traced back to both significant or trivial waking events. It is therefore understandable that, either due to public information or direct experience, some people have experienced recurring nightmares featuring global unrest. Even dreams more specific to individuals can increase in intensity in response to increased anxiety, which matches the change to dream content reported by some individuals.

However, conclusions we draw about dreaming are all tentative. Much of research that has been carried out is vulnerable to unusual data due to the effects of subjects experiencing poor sleep in a laboratory environment or is limited by our technological capabilities. Whilst electroencephalograms are often considered to be the ‘golden standard’ for assessing brain function, they cannot pick up some smaller but important groups of neurones such as the raphe nucleus, which is involved in modifying serotonin levels to achieve changes between the ‘sleep’ and ‘wake’ states. Finally, existing models such as the Activation Synthesis Theory depend upon the central assumption that all dreaming occurs during the REM phase of sleep, whereas this study shows that this is likely not the case.

As people around the world continue to self isolate, our daily patterns of living are continuing to shift. However, we are currently reliant on self-reporting and personal recollections as the primary source of information as to how this could modify our sleeping habits, and hence how we dream.

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / News in Brief: humanoid chatbots, holiday specials, and harmonious scholarships21 December 2025

News / News in Brief: humanoid chatbots, holiday specials, and harmonious scholarships21 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Lifestyle / All I want for Christmas is a new hanukkiah22 December 2025

Lifestyle / All I want for Christmas is a new hanukkiah22 December 2025