Marmite, mayhem and free will

Drawing on evidence from quantum mechanics and behavioural neuroscience, Rory Cockshaw explores the role of science in furthering our understanding of free will.

Edward de Bono, the originator of the term “lateral thinking”, has a unique remedy for the Arab-Israeli conflict, which falls well outside the bounds of the typical one-state/two-state solutions.

His idea is quite simple: Marmite.

De Bono’s reasoning is as follows. In the Middle East, deficiencies in zinc are very common, partially due to the consumption of unleavened flatbreads. Zinc deficiency can cause aggression. Marmite, being yeast extract, is incredibly high in zinc. Thus, it follows that importing plenty of Marmite to the Middle East could serve to stem the fighting - at least, according to de Bono.

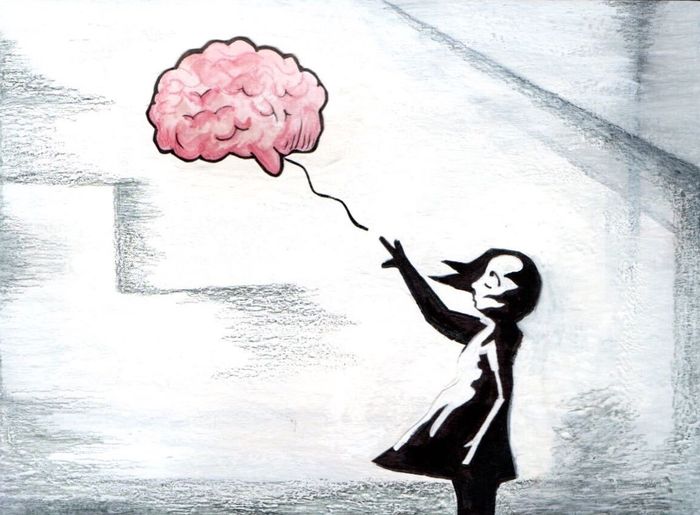

The key point is this: the decisions we make may not be as free as we’d like. De Bono’s hyperbolic take aside, nutrition, living conditions and other environmental factors undoubtedly play a key role in determining our seemingly “free” behavioural choices.

“Free will” is a contentious topic, so I’ll define it right from the start as the state of being able to have done otherwise, were the clocks turned back but everything else kept the same. This is the interpretation I’ll be sticking to throughout, though others are possible.

“Causal determinism”, on the other hand, is the idea that every event is purely the product of the initial conditions. The French Enlightenment polymath Laplace imagined a “demon” that, if it had total knowledge of the entire Universe in the present, could flawlessly retrace the past and predict the future.

Free will, under my interpretation, and the determinism of Laplace are thus incompatible, and the competing theories have been locked in a power-struggle for millennia. Modern science is only now, at its most cutting edge, approaching a resolution in two different ways: through quantum mechanics, and behavioural neuroscience.

Quantum mechanics and free will

Probably the most common attempt to refute determinism with modern science is an appeal to quantum theory. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, for instance, states that there is a limit to how precisely you can know any pair of quantities. One cannot know both position and momentum exactly, it posits; nor can you precisely know both the energy and the time at which you measure the energy of a particular particle.

"Why, then, would we assume that consciousness (presumably macroscopic) and free will are affected in any way by the quirks of subatomic quantum theory?"

In short, Heisenberg tells us that things are fuzzy. This isn’t because of faults with our equipment, either; the Universe just works like this. Combine this with ideas like wavefunctions and wave-particle duality, and things get really fuzzy.

According to quantum mechanics then, the Universe at the most fundamental level does not behave nicely, simply, or predictably, and therefore cannot be deterministic. As a result, free will is allowed. Or so you might think. Anyhow, here are three objections to that theory.

1. Quantum mechanics predicts the probabilities of various outcomes. Though non-fatal to the idea of free will, this fact restricts how free that will is. If the clocks were wound back and all other factors kept the same, and some event repeated, an agent could indeed act differently than they did the first time, though some actions would be more likely than others. According to my definition of free will, then, this objection is merely limiting, not falsifying.

2. Lack of determinism does not imply free will, as has been supposed until this point. Firstly, compatibilism (the view that free will and determinism are compatible ideas) is perfectly valid according to different definitions of free will. Secondly, if I were to be subject to perfectly random tics (more random than Tourettism, in which tics are picked up at least somewhat deterministically), this would negate determinism (because they are random), yet would in no way imply free will (because they are uncontrollable). A similar consideration applies to quantum mechanics: it may be random, thus negating determinism, but doesn’t imply free will. It’s possible to have neither, just not both.

3. Bohr’s correspondence principle states that quantum mechanics, when applied on a large scale, predicts exactly the same world as classical mechanics. In other words, the two theories begin to converge when you leave the micro and enter the macro. Why, then, would we assume that consciousness (presumably macroscopic) and free will are affected in any way by the quirks of subatomic quantum theory?

As we can see, the quantum mechanical argument against determinism does not imply free will (though it certainly doesn’t reject the possibility). We might have better luck taking the problem in the opposite direction with neuroscience.

Neuroscience and free will

While the philosophy of free will goes back at least 2500 years, the neuroscience of free will goes back only a few decades to Benjamin Libet in the 1970s.

"Perhaps some of our choices aren’t freely made, but they are freely alterable between decision-making and execution"

Libet showed that a certain “readiness potential” that precedes voluntary motor movement - the Bereitschaftspotential - begins around 400 milliseconds before a participant registers having made a conscious decision and around 550ms before the action itself. More recent tests have resulted in lag-times between readiness potential and conscious decision of up to 10 seconds, and it’s now even possible to predict which hand will move.

If our brains are readying themselves for our decisions seconds before we know we’ve made them, how can we ever defend free will? Here are three arguments once again, which this time counter the position that free will is indefensible in the light of neuroscience.

1. With time differences on the order of milliseconds, it’s possible to criticise the results on an experimental basis. How accurately can you pinpoint the time at which a conscious decision is made? How much lag-time is introduced by the participant delaying between consciously choosing and indicating that they’ve done so? However, this objection is weakened somewhat for larger lag-times of up to 10 seconds, so a stronger case is needed.

2. Tests thus far include simple, binary decisions such as choosing between raising the right or left hands. Such experiments might not show evidence of free will, but how about free will in the context of complex social situations where possible behaviours are not binary but multifaceted and minutely detailed? Even if free will were conclusively rejected in a button-pressing experiment, it would mean nothing for free will in the “real” human experience.

3. Libet himself never interpreted his findings as rejecting free will. Evidence shows that consciousness has the ability to veto the Bereitschaftspotential up to the last moment - termed the “free won’t”. Perhaps some of our choices aren’t freely made, but they are freely alterable between decision-making and execution, which still satisfies my definition of free will.

Quantum physics and neuroscience have yet to yield any dependable results regarding the existence of free will. My personal hunch is that we do live in a far more determined Universe than we often care to imagine, as de Bono’s hypothesis of Marmite and mayhem so perfectly exemplifies.

However, the jury is still out; so, in the words of Ludwig Wittgenstein, “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025