‘BME theatre in Cambridge is an allyship: we must work together’

“There’s a ripping irony to the statement that ‘talent is more important than skin tone’. That’s exactly what Teahouse, Macbeth, and subsequent BME productions have been about.” Siyang Wei and Saskia Ross respond to Christian Harvey’s critique of the term ‘BME’ in Cambridge theatre

Recently, an article was published criticising the use of the term BME in creative circles, which quickly devolved into a disparaging review of ‘BME’ productions in Cambridge theatre. The article makes some good points: for example, the homogenisation of ‘BME’, when actually a role should be specific to a particular race or ethnicity, is in fact one of the things that people working on BME theatre are trying to prevent.

Some headway was made into this issue at an open meeting last Easter between BME students and representatives of dramatic societies (such as CUADC, Marlowe and the Footlights) where we discussed adding a point into the constitution which would prevent such generalisations in future productions. It is an element that stems from the whiteness of Cambridge theatre that BME theatre is, in fact, actively trying to tackle.

This point in particular highlights the apparent general lack of knowledge about what has actually been happening in BME theatre - an ignorance that the article seems to betray. There are criticisms that can be made of ‘BME’, but what it means in the context of Cambridge theatre is an allyship, because there are simply not enough of us for us not to work together.

‘BME’ is an alliance against the problem of whiteness, which already Others us. We can talk about how white creatives might sometimes misfire when attempting to increase diversity in their shows. This could be a productive discussion; indeed, it is also another reason why BME theatre is still necessary. However, it is not accurate to paint this as a problem with BME theatre itself.

Ultimately, we do not disagree with Christian Harvey’s vision. In an ideal world, BME actors would not be Othered and there would be no need for BME productions. But this is not the world we live in: racism and whiteness are still hugely powerful forces in modern British society.

When we were freshers two years ago, before BME theatre really began to pick up any momentum, there were very few BME people active in theatre. Aside from Saskia, there was one black female actor and no black male actors. There was one Asian person who sometimes did musical theatre; in that year’s CUMTS Gala Night, he sang the part of Seaweed Stubbs, a black man, in a song from Hairspray, at least partially because there were no black male actors who were available to do so. BME theatre is not a club of people banding together to Other themselves; it’s a group of people who have continually been Othered making a space that is explicitly for ourselves.

There is no shortage of Shakespeare in Cambridge, but there has most certainly been a shortage of BME actors involved in Shakespeare. One of the key problems of BME participation that we have identified from speaking with many BME students is that the barriers to entry tend to be a lot higher. BME people in general are less likely to have previous experience of theatre, are likely to have fewer roles open to them, and are far more likely to feel uncomfortable in theatrical spaces.

Even when roles are technically open to everyone, the experience of putting yourself out there can be alienating for BME people. Xelia Mendes-Jones, a third year student who has been active in the theatre scene since her first year, described the problem as it was two years ago as “endemic”.

“Ultimately, we do not disagree with Christian Harvey’s vision. In an ideal world, BME actors would not be Othered and there would be no need for BME productions. But this is not the world we live in”

“Of my nine productions as a fresher, I was the only BME actor in eight of them, let alone narrowing my ethnicity down to Indian. The reason for this was not that BME people were drawn to BME-only productions and thus, away from ‘normal’ productions; there were no BME-only productions that year. At the Macbeth afterparty we became abundantly aware that people don’t audition because of the futility they feel. When you show up and realise that you’re the only non-white person in a room of 20 hopefuls, you feel like you wouldn’t have a place in the show.”

“There’s a ripping irony to the statement that ‘talent is more important than skin tone’. That’s exactly what Teahouse, Macbeth, and subsequent BME productions have been about.”

Jay Parekh, a student who has recently broken into the creative scene, affirms the importance of BME theatre in broader aspects of life at Cambridge: “I don’t think I would have become so into making films and photography as I have without gateway opportunities.” He makes particular note of the BME art exhibition he has organised for Lent term in collaboration with the BME Campaign, and says that it might not be happening if not for his involvement in BME specific projects.

Saskia and I both participated in the first BME Bar Night hosted by CUMTS, alongside a number of wonderful performers who had never been involved with musical theatre before. They invariably said that the only reason they had felt comfortable enough to audition for and participate in the event was because it was specifically for BME people. This story is true of all other BME initiatives in the past year and a half.

Last Michaelmas’ production of Teahouse featured around 20 East/Southeast Asian actors, the vast majority of whom had never been involved with Cambridge theatre before and a number of those have gone on to participate in other projects that are not specifically for BME people. The following term’s BME Macbeth had over 50 auditionees, almost all of whom had decided that they wanted to be involved in any capacity due to it being a BME production. Many of those who were not successful in their auditions then went on to apply for production team roles, simply to be a part of what was an incredibly heartfelt project.

Harvey’s accusations of ‘ghettoisation’ and ‘Othering’ of the actors therefore particularly struck us. To say that a stage full of BME people is ‘ghettoised’ is especially concerning and plays into a perspective of whiteness that we had not expected to be touched upon in this article. Here, Harvey inadvertently highlights one of our main missions: to make a stage of BME people the norm, not to have preconceptions of ‘ghettoisation’ in non-white theatre, and to be afforded the blank slate and reasonable expectations that theatre currently enjoys.

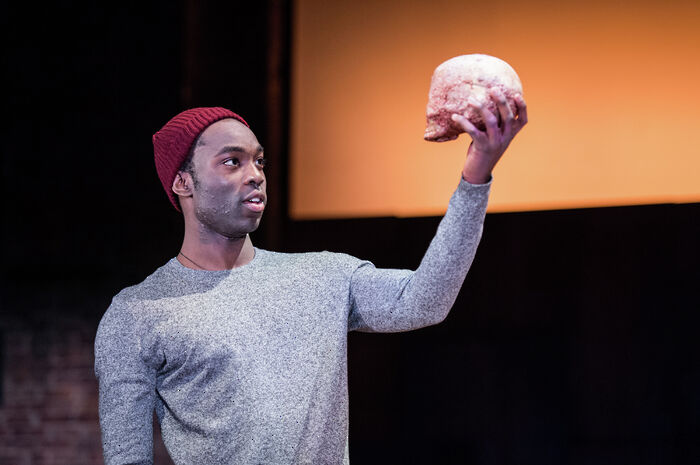

Harvey appears to believe that we are past a time where BME people are underrepresented in the British acting world at large, naming Riz Ahmed, Paapa Essiedu, and Benedict Wong - two of whom can only generously be described as moderately famous; one of whom is mostly known for acting as the lead in a West African-inspired adaptation of Hamlet overwhelmingly featuring black people, and none of whom went to Cambridge.

Naomi Obeng has already written a series of articles for Varsity examining the whiteness of Cambridge’s theatre scene and its relationship with the British drama industry. At the same time, Harvey discusses his experience of being cast in a ‘BME’ role that was written and, presumably, directed by white people. This is a problem, and is exactly the thing that BME theatre hopes to change. We hope for a Cambridge theatre that de-centres whiteness enough that specifically BME projects are no longer necessary - where it is par for the course for stories about black people, stories about Asians, migrants, refugees and marginalised people of all kinds to be told on the Cambridge stage such that they are no longer especially exciting, but routine. We want an all-white cast to be jarring and shocking to the audience at large. We are not there yet.

What we fear the most is Cambridge’s institutional tendency towards short-term memory - that as soon as the current cohort of students supporting BME theatre have left, there will be nobody to carry on the project. What Harvey’s article does is survey the situation as it currently stands: the result of over a year of hard work by BME students, and say that it’s good enough that the efforts that brought us here were never necessary.

BME theatre, like any other remotely progressive project, is an effort that requires a huge amount of work to retain any ground at all. If we relax or forget, we will be here in ten or fifteen years having to start all over again

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025