David Edgar and the state of playwriting

This year David Edgar gave the English faculty’s annual Judith E Wilson lecture, Flora Bowen discusses the evolution of playwriting in Britain today

Conjure the scene: the playwright. Who, or what, do you imagine? A lone figure scribbling at a desk, clothed in half-darkness and shabby corduroy; an ale-swilling, breeches-bedecked Jacobean Company; a stern-faced pitch-black art “collective”? On this January day in Cambridge, where ice touches puddles and faces, students, writers, and academics bundle into the English faculty to discover playwriting, and its evolving shape in Britain today.

“Over the last 60 years the great questions of British society have been more consistently rigorously and durably confronted in the theatre, than anywhere else”

The figure on the stage is not draped in cobwebs, nor recounting a classic night out with Shakespeare and Johnson, nor breaking the fifth and sixth walls in Brechtian monologue. He is David Edgar, one of Britain’s leading playwrights, whose works have sparked life across all the major theatres of the U.K, on stage, screen, and film, as well as internationally. Political discourse, and adaptations inspired by Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson, have provided great commercial successes; he comes to Cambridge from his knockout RSC adaptation of A Christmas Carol – but his more than sixty published and performed works are rich in their scope and range. For any Cambridge student dreaming of a career carved out through writing, his life and CV provide hope.

Hope is to be found in abundance in the vibrant playwriting and theatrical landscape of Britain. According to Edgar, “over the last 60 years the great questions of British society have been more consistently rigorously and durably confronted in the theatre, than anywhere else”. The “angry young men” of the fifties and sixties; the collapse and disillusionment of post-war British society; women’s place in society; the ever-increasing demand for works that speak to BME questions; the “triple threat of aids, drugs, and Thatcher”; and today, in the 2010s, the war on terror, and questions of identity.

“The play-text is both a blueprint and a record, but also has an independent life”

In this outpouring of questions and confrontations, Edgar set up camp in the realm of seventies’ theatre – which he remembers as “an extraordinary time”. The abolition of theatre censorship in ’68 expanded the subject matter and languages available to writers; improv work took off; an influx of hitherto banned theatre companies swept into Britain from the continent and beyond. This hubbub of activity was centred in a network of small theatres below and above pubs and clubs: the underground, the alternative, the fringe. Theatre companies were set up in the backs of unreliable Ford transits, collaborations forged not only with new faces, but with new forms of avant-garde theatre. It was here that Edgar started to understand the role of writing in theatre: “The play-text is both a blueprint and a record, but also has an independent life.”

Artistic ambition developed in parallel to literary advances, and Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn, at the National and RSC respectively, opened up their theatres to new work, new writers and new theatre-goers, encouraging the overthrow of bourgeois institutions. Theatre Writers’ Unions expanded, better contracts were negotiated, and drama departments across the country challenged and informed new generations of students.

“An individual playwright cannot address the problems that face the contemporary world”

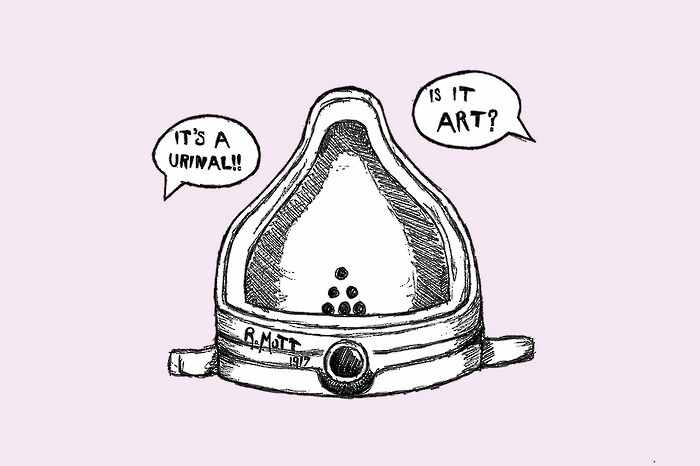

The dominance of the playwright in a work began to be called into question, with RSC director Ben Power crudely stating: “I’m not interested in the idea of someone sitting in a room writing something which is then handed out to someone else to direct.” Post structuralism and the influence of Jacques Derrida on the theatre challenged the “moribund concept of a single meaning authorised by the playwright”.

Rather, theatre companies started to experiment with different forms and methods of scripting, offering site specific productions, democratising the creative process, as actors gained greater freedom to influence their work, and creating plays that would allow the reader to make a number of decisions for themselves. All such innovations worked, Edgar says, to end the perceived problem that “an individual playwright cannot address the problems that face the contemporary world”.

And what now? Edgar states of the 2010s that we are living in a “golden age of playwriting”. The so-called “Death of the Playwright”, he ventures, has been greatly exaggerated. In 2013, more new work was being shown than revivals, for the first time in at least 100 years, representing 69% of “straight theatre” and 59% of all professional productions. This growth is supported and developed by innovative publishing companies, the growth of digital marketing and publishing, making play scripts as accessible as cookbooks or celebrity biography.

Theatre focuses on documentary, in the growth of testamentary verbatim theatre to try and make sense of the war on terror, and questions of personal identity. British theatre is a world that extols political, cultural, and ethnic diversity. For Edgar, looking back on this extraordinary 70 years, what truly marks great political plays of this period was that they “were new, modern, and had something against the government.” Yet, in spite of all the renewals and shifts in playwriting, Edgar considers it absurd to argue that writing is on the way out. The script, he says, is the thing that both starts and ends the process. The text, after all, is the thing that survives.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025