Denis and Katya: Inescapably compelling and harrowing

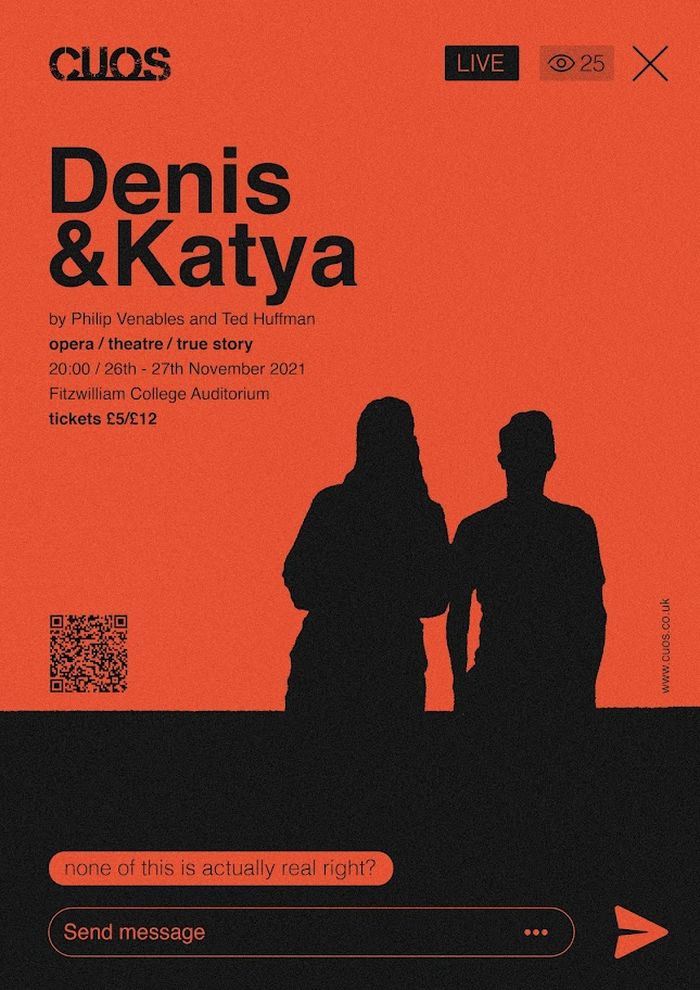

Benji de Almeida Newton reviews CUOS’s production of Phillip Venables and Ted Huffman’s ‘Denis and Katya’

There are few greater testaments to a show’s success than the audience being speechless after its opening performance. The lights went up, the audience stayed in their seats, and after a few moments looked sheepishly at one another with the embarrassment of being moved, the jarring experience of being transported back from the scene of the crime to the Fitzwilliam Auditorium. In fact, I probably should have prefaced this review by saying that it is one of the most moving productions of any kind I have seen at Cambridge.

The opera opens, however, from a place of urgency. We are confronted with a narration of the events leading up to the stand-off between Denis and Katya, two teenagers in the town of Pskov, and Special Forces. Maxim Meshkvichev and Hannah Dienes-Williams get the audience up to speed on events in a matter-of-fact, sometimes urgent sometimes newsreader-y way. It feels we’re being given a forensic report for an incident which gradually peels back in sinister realisations. There is a profound sense that the two characters have to tell the story no matter what, that the audience must never look away nor lose a moment of attention. And indeed we do not. Meshkvichev and Dienes-Williams manage to make it so that the audience simply cannot look away. This is made possible too by the cellos, two on each side of the stage, whose lethal precision and careful concentration provide every musical and dramatic texture conceivable to drive the opera to its devastating conclusion.

“There is a profound sense that the two characters have to tell the story no matter what”

Although by nature a commentary on the voyeurism of tragedy and its news coverage, the tale itself is told sensitively and compellingly. Six characters (Journalist, Friend, Teacher, Teenager, Neighbour, Medic), all played by Meshkvichev and Dienes-Williams, bring forward the intersubjective dimensions of the story, and each voice is made enjoyably distinct not only by their generous acting, often in both Russian and English, but by the technical wing of the production. Denis and Katya heavily relies on being able to display extensive WhatsApp conversations and video projections. The very dramaturgical fabric of the show requires exact lighting and textual display changes, which were carried out utterly seamlessly by Fin Scott and Ella Fitt.

It is worth reiterating that what made this production so successful was the relentlessness with which it captivated the audience’s attention. At times it was breathless, the details of the story overwhelming, scarcely allowing the audience to gather their reactions, and importantly judgements, as each new detail was revealed. Each character’s perspective came with a different lighting and musical flourish in rapid succession, with the result that Denis and Katya – characters mentioned to but never seen – take on a three-dimensional quality almost immediately. Under the dramatic direction of Oscar Simms, the spoken and sung monologues bespeak clear emotional arcs which build with well-judged tension over the course of the opera. What starts out as matter-of-fact account descends into a visceral melodrama, in keeping with the original sense of the word: the height of pairing music and drama. The last quarter or so of the opera, just when you think there is nothing left to tell, no angle left to be explored, comprises a folksong-like section where shocking details of media coverage come to light against a panoramic shot of a pine forest. Without giving too much away, Dienes-Williams’ last procession across stage reminds the audience of the physicality of a crime which has thus far only existed as an account. It’s an ambiguous moment of catharsis, treading safely below the line of histrionics, and realises the emotional weight of a retelling which one gets the impression was so far carefully restrained.

Musical directors Jess Hoskins and Rosie Dunn turn the cellos into a kind of chorus – their presence is as much a staging consideration as it is musical. Each cellist is mesmerising, locking the music with extraordinary instincts of ensemble into the central square. Each navigates successfully between moments of frenzy and delicacy, blending with electronics operated with great effect by Will Audis. The atmosphere this opera manages to create, like many of the perilous situations on stage, is inescapable.

I have little else to add except that you must go and see it. This is Cambridge opera at its most ambitious. It is opera at its most harrowing.

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025 Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025

Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025