‘The harvest is in’: maternal grief and stylish revenge in Agamemnon

This outdoors production of family grief under the night sky at Leckhampton House is hauntingly atmospheric

Against the haunted and uncanny backdrop of Corpus Christi’s Victorian-era Leckhampton House, Klytaimestra eagerly anticipates the return of her murderous husband Agamemnon from the Trojan War.

Agamemnon has sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, Klytaimestra’s “birth pang”, to appease the goddess Artemis who he has offended, and Klytaimestra intends spectacular revenge. Anne Carson’s poetic and electric translation of Aeschylus’ tragedy is reason enough to visit the theatre, but this production performed outdoors in the growing and eerie dusk is a feast in its own right. Director Mia Hull has captured the searing depths of Carson’s sometimes beautiful, sometimes violent language, yet has injected the play with her own unique and stylish vision.

“This production perfectly encapsulates the sensation of being haunted by one’s own mind”

If Agamemnon is a play about the shameful sins of the past coming to bloody fruition in the present, this production perfectly encapsulates the sensation of being haunted by one’s own mind. Throughout the production, each stately window of Leckhampton House becomes mysteriously lit, glowing orange in the approaching dark of night. These imposing windows are frequently visited by fleeting, ghostly silhouettes, whose mute shadows taunt an audience unsure of what character lingers behind the apertures.

With design by David Hurtado and Hull, the withered and aged bricks of Leckhampton House become possessed by a sense of the otherworldly, an atmosphere conjured through the ambiguous presence of a mute character named Ghost Child (Siew Yen Loke), who delicately stalks the stage. Before the performance commences, Loke can be found curled up against a stony pillar, her face covered with a thick, dusty residue threatening to absorb her into the Victorian brickwork. Prevented from emoting with her face due to heavy makeup, Loke is excellent at embodying the childish longings of ghostly Iphigenia, who is not yet ready to depart from her father and mother. Despite her father being her murderer, Iphigenia tenderly gravitates towards his imposing body, not letting him forget her.

“By manipulating him into trampling the red carpets, she creates a public spectacle of his shame”

The play begins to truly dazzle with the long anticipated reunion of Agamemnon and Klytaimestra, a doomed couple expertly embodied by Michael Schwimmer and Zoe Bond. As opposed to waiting patiently for her husband to return from war, as was generally custom, Klytaimestra ruptures gendered etiquette by enlisting her own watchman to bring her news of Agamemnon’s return. From the beginning, Klytaimestra is thus one step ahead of Old Man (Peter Simmons) and Young Man (Joshua Herberg), the councillors of Argos who stand no chance of sullying her bloody theatrics. Klytaimestra’s revenge begins before the murder, with her idolatrous overpraising of Agamemnon, who she humiliates with gestures of caricatured, disproportionate reverence. Agamemnon’s ill-fated entrance to the site of his murder is deliciously drawn-out, as Klytaimestra gradually assembles a portentous red carpet which she implores Agamemnon to tread upon. The production perfectly encapsulates the symbolic gravity of this sequence: by forcing Agamemnon to walk upon the “crimson cloths″, Klytaimestra forces her husband into publicly desecrating a special tapestry that Greek audiences would have recognised as representing the couple’s marriage bed. For Klytaimestra, Agamemnon, the adulterous murder, has symbolically stained their nuptial bed, so by manipulating him into trampling the red carpets, she creates a public spectacle of his shame.

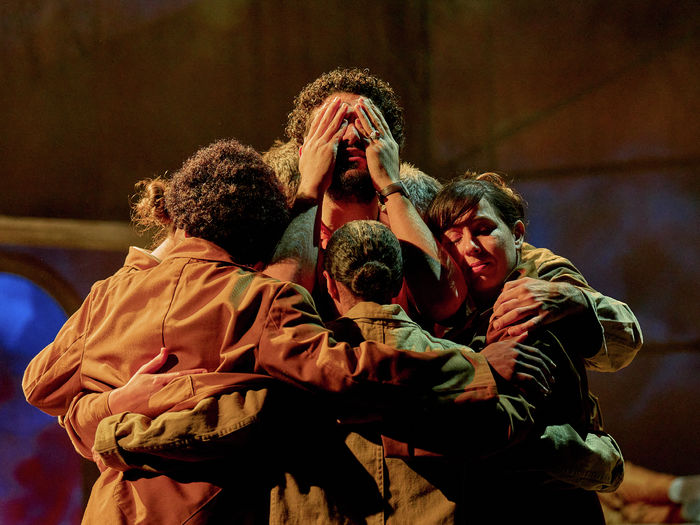

Schwimmer’s performance as a patriarchal abuser was chilling in its scarcity. With shielded eyes and unwavering self-control, his body language was menacingly reserved, rendering him all the more terrifying. There were moments at the beginning of the play where the statuesque stillness of the cast demanded a lot of the audience; with their sparing use of gesture, it was easy to get lost in dense and confusing dialogue of Greek tragedy. Nevertheless, as the play proceeded, the suppressed, muffled machinations of the actors seemed to pay off: at the play’s climax, when I expected a scene of murder, the actors burst into a performance of gorgeous choreography. This ensemble dance sequence radically shifted the atmosphere of Leckhampton House: as the unrelenting, punk-inflected rock of Incendie by Ménades boomed from speakers, the bitter resentment which possessed the characters was channelled into ecstatic, jovial release. Hull has written that her vision for Agamemnon drew from a Tadashi Suzuki and a Pina Bausch physical practice, suggesting her philosophy of theatre is interwoven with a theory of the body as a locus of shocking viscerality. Hull’s daring creativity completely paid off. Her decision to investigate ancient murder through the jarring and spiralling movements of the cast complicated the moral landscape of the play, as fated enemies danced together in rough and sensual relationality.

The production hinges on the intimacy and inseparability between creation and destruction. Klytaimestra’s cold-hearted revenge refuses to promise closure, and threatens to unravel into cyclical, unending violence. As the house’s entrance becomes strewn with the remnants of fragmented carpet and the deceased bodies of Agamemnon and his prisoner of war, Kassandra (Sylvie Field), the stone ground becomes a cluttered zone of theatrical disarray. Old Man and Young Man haphazardly and clumsily illuminate the stage, exposing the corpses with huge orbs of beaming, painful light. In the wake of the violent chaos reaped by her parents, a lone Iphigenia punctuates the close of Agamemnon, continuing to haunt the grounds of Leckhampton House. The production’s mobilisation and re-imagination of space was a true triumph, granting this Ancient Greek tragedy a stylish, vibrant immediacy. I found myself imagining what lingered beyond the house’s grand facade, which itself became a key actor in this unforgettable play of domestic betrayal and revenge.

Agamemnon is playing at Leckhampton House from Thursday 18th to Saturday 20th May, 8:30pm

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025 Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025

Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025 News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025

News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025