Shakespeare: in and out of class

Ahead of a term of Shakespeare studies, Elsie Hayward ponders the benefits of seeing the Bard staged by Cambridge students — and what could be improved

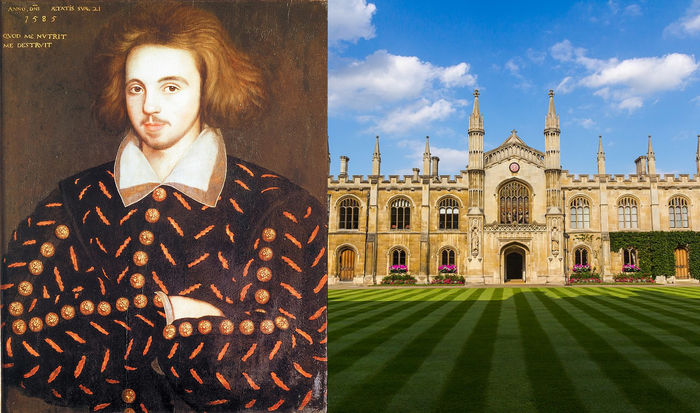

This Lent term I saw three different student productions of Shakespeare plays in Cambridge; as a first year Engling, I’ll be studying nothing but the Bard in Easter term. We can’t seem to leave him alone. But what can student productions contribute to Shakespeare’s legacy? And how does he span both the teaching rooms and the stages of Cambridge?

I’ll be honest: my small sample of Cambridge Shakespeare has not left me completely satisfied. I realise this won’t be representative of the Cambridge theatre scene as a whole, but I think that it exposes a problem we encounter with putting Shakespeare on stage. I wasn’t blown away by BME Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, for example, because it prized style over substance, and didn’t quite pack the vital emotional punch. In contrast, Romeo and Juliet in Trinity Chapel featured strong performances but seemed to lack a creative vision big enough to make such a well-hashed text feel truly electric. You only need to flip through past Varsity reviews of Shakespeare to see that audiences appreciate bold choices and innovation. The negative reviews seem to have something in common — a desire to be shown something new in these texts. The worst criticism of last summer’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was that it was boring; by contrast, the best Shakespeare I’ve seen in Cambridge was Macbeth in the Round Church, mainly because it was bold and inventive. I had never imagined the banquet scene as the characters sitting in a circle on the floor and eating colourful fruit with their bare hands; there is a reason to do Macbeth again.

“Student theatre is meant to be about excitement and experimentation”

No one can escape studying Shakespeare in school, and I wouldn’t blame anyone if that were enough to stop them from seeing the life in his plays. But we should never forget that they were written to be performed. It wasn’t just a cop-out if your teacher made you watch Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet in class. To really appreciate Shakespeare, you have to see it live and breathe; you have to hear those words sing. For these reasons, it’s great to see that student theatre keeps coming back to Shakespeare. But maybe something is missing.

Maybe we are still too much in awe. Maybe that’s the fault of the way Shakespeare is taught, and the environment in which we all study. But when it comes to bringing Shakespeare to the stage, reverence is a trap. If you want your production to have life force, you have to treat the text as if it does too — living things are supposed to change and face reinvention, so the only real commandment from the Bard to us is keep it alive, and that means being brave. We can look to the professional theatre for inspiration; I haven’t seen anyone bring out the timeless vitality and irrepressible energy of these plays better than Emma Rice. Her Romeo and Juliet compellingly drew out the crazed heights of teenage passion and she brought out a comedy in A Midsummer Night’s Dream that genuinely worked for a young modern audience, so it’s no coincidence that she was able to draw in young people.

“To really appreciate Shakespeare, you have to see it live and breathe; you have to hear those words sing”

There may not be a right way to do Shakespeare, but playing it safe certainly isn’t it. I can forgive many sins in the name of innovation and experimentation; I can’t forgive Shakespeare being made boring, because he isn’t. If someone had an interesting idea and it didn’t quite work out, then I’m not displeased on Shakespeare’s behalf. But having an interesting idea is the only qualification you actually need to approach a Shakespeare play, when most of them have been done so many times before (and, let’s face it, they’re all really old). We’ve seen that it can be done — Cambridge has witnessed two fairly radical productions of Romeo and Juliet in the past year (the Cambridge American Stage Tour and the Marlowe Arts Show). Whatever problems reviewers had with them, they didn’t seem to resent risk-taking. In fact, Varsity reviews for both acknowledged the trap of staging a play that has developed some kind of built-in cliche, and the need to break out of this. The same applies to the European Theatre Group’s bold production of The Tempest, which was very well-received.

Student theatre is meant to be about excitement and experimentation anyway. I don’t think it’s hubris for us to take on Shakespeare. Fresh thinking and energy can unlock so much in these plays. So maybe the secret is to relax and let our imaginations really work, and that is where the boldness and bravery will come from. I think that’s what we really owe a great legacy. And if it goes wrong, don’t worry about the texts: Shakespeare is bigger than you, and he can take it

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025