Everything you should read, that you’ve never even heard of

Following her takes on canonical texts, Molly Scales unveils the hidden gems of her English degree

If you’re anything like me, you’ll occasionally stumble across one of those ubiquitous ‘100 Books to Read Before You Die’ lists. If you’re everything like me, you’ll resent those lists with a fierce, unyielding hatred. Who are you to tell me what I should and shouldn’t read, BBC Culture? Why should I listen to you, highly respected Guardian correspondent? How dare you open my eyes to the greats of the literary canon, I think, wondering who this so-called ‘JSTOR’ thinks it is.

My point is: I’m not going to try and guilt trip you into reading anything you don’t want to. Heck, I’m not going to guilt trip you into reading things you do want to. What I am going to do is humbly place a few offerings from my degree at your feet. Take them if you so desire. These aren’t books you should read before you die. Some of them may, in fact, be the very reason you die. These are instead the hidden delights of my English degree; they’re the texts I wouldn’t have stumbled across were it not for 3am nights in the library, strange forays into the wilderness of Internet Archive, or plain curiosity. Think of me as your even-more-neurotic White Rabbit (most of these were indeed found when I was late, late, for a very important date – hello essay deadline).

“These aren’t books you should read before you die. Some of them may, in fact, be the very reason you die”

Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure by John Cleland

Before there was Fifty Shades of Grey, there was the dizzying kaleidoscope of colour that is Fanny Hill. Written in 1748-9 by an author on the verge of bankruptcy, the first erotic novel solved its author’s financial difficulties… until it landed him in a series of criminal trials over the indecent material of the text. It’s a total romp through eighteenth-century sex work and courtship, with textual queerness in abundance. Just come prepared for some excruciatingly awkward supervisions.

Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth is so iconic (and campy) that he stands alone as having been awarded the highest honour a writer can hope for: a cameo in BBC Merlin. It’s no surprise. Historia exists in the delightful space where it’s definitely fiction, but the author is desperately trying to pretend he ‘found’ these papers and they’re absolutely, totally historically accurate. Even the bits about the dragons.

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara

I read Che Guevara’s scrappy account of his travels across South America while hopped up on Ibuprofen, Benadryl, sleep deprivation, and student cooking that can only be described as edible. I did not, as such, expect to feel an overwhelming kinship with one of the most influential revolutionaries of all time. But reading Guevara’s grapplings with a single cantankerous (and broken tank-erous) motorbike, his pretending to be a leprosy expert to aid his passage, and pitching up looking for work in a Miami bar, you realise… he was just some bloke. Brilliant, chancing, compassionate; not the political powerhouse he would later become. It’s an exercise in humanisation – and deeply, unavoidably human.

“It’s an exercise in humanisation – and deeply, unavoidably human”

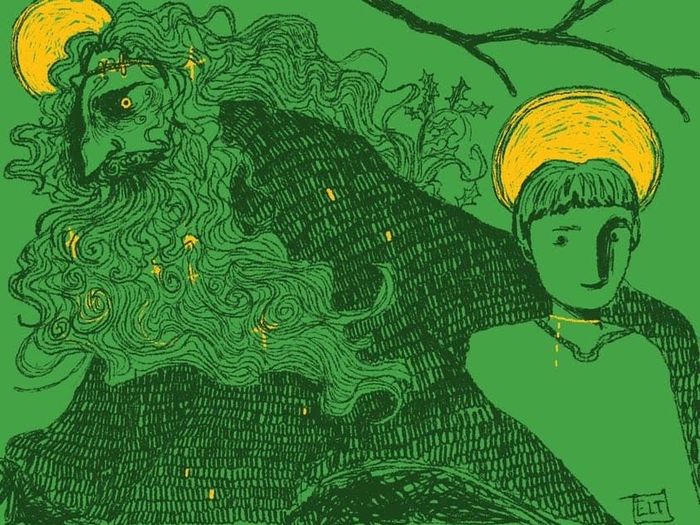

Gallathea by John Lyly

Ever wished Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was queer (er)? Look no further than John Lyly’s Gallathea. Set in a quaint pastoral village, the story unfolds upon maidens Phillida and Gallathea disguising themselves as shepherds to escape being sacrificed to a big ol’ sea monster (surprisingly apt metaphor for the patriarchy). Do you see where this is going? No? Remember it’s an Elizabethan drama. Got it now? He was a boy that was actually a girl and she was a girl that was pretending to be a boy. Could it be any more obvious?

“You know how it ends: he was a boy that was actually a girl and she was a girl that was pretending to be a boy. Could it be any more obvious?”

The Rape of Lucrece by William Shakespeare

“Hey, have you heard of this really indie writer? He’s kinda underground, you’ve probably not heard of him. Yeah, his name’s William Shakespeare.” That’s what putting Shakespeare on a ‘hidden gems’ list feels like. At least this one’s a deep cut? It earns its place on here because The Rape of Lucrece is one of the Bard’s least trodden texts, in what is nearly as great a miscarriage of justice as the text describes. Lucrece may cry “this helpless smoke of words doth me no right”, but it certainly “doth right” to readers willing to give it the attention it deserves.

The Female Husband by Henry Fielding

It will take you twenty minutes, maximum, to read. Go do it now. Why are you still reading this? Fine, if you still need convincing: Henry Fielding knocked the pamphlet off immediately after the real-life trial it’s based on, that of Charles Hamilton for vagrancy. Doesn’t sound like much, does it? Well, ‘vagrancy’ is a sort-of placeholder for Hamilton’s habit of tricking women into marrying them by pretending to be a ‘husband’ despite having been assigned female at birth. The only reason they were caught out in Fielding’s version? Hamilton’s third wife’s mother didn’t believe it was possible for a husband to make his wife so happy, unless they were secretly a woman. And she was right. You can’t make this stuff up. And Fielding didn’t.

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025

Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s gossip culture is a double-edged sword7 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s gossip culture is a double-edged sword7 April 2025