Communion in a coffee shop

Amie Brian questions the slow secularisation of religious spaces in Cambridge, wondering whether this shift might offer something sacred

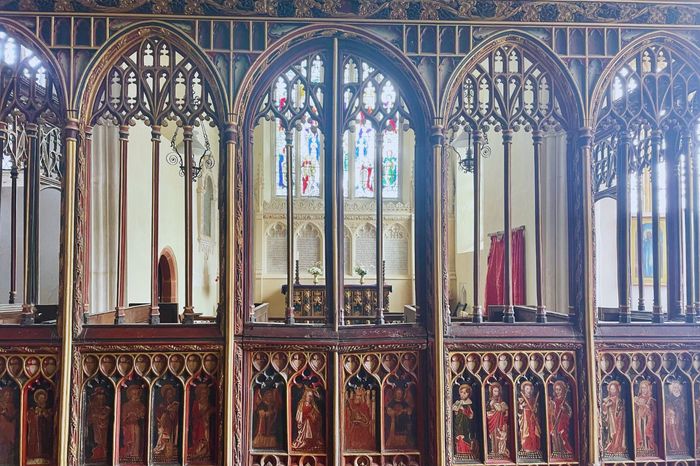

Nestled into the side of Trinity Street sits the distinguished form of Michaelhouse Café, a towering mass of ancient stone. The first written record of St. Michael’s Church, as it was formerly known, dates from 1217, although historians suspect the building is even older. Across its history, the Church served as Chapel to three colleges: Michaelhouse College, Gonville, and then Trinity.

Its steeple, however, is not an idiosyncratic sight in Cambridge – in the city centre, you’re never more than 500 metres from a church, and there are 39 Christian churches in Cambridge. It is, perhaps, emblematic of how secular and religious thinking have always co-existed and interacted in Cambridge.

In fact, the city may have more churches than it knows what to do with, and this is indicative of a larger trend. There are 16,000 churches in England, and many of them run services with empty pews. In contrast, Michaelhouse Café stands out for the variety of roles it serves its local community. In it, the secular and religious collide – behind glass doors, it houses an active chapel, occasionally a site for book sales. But it is also a community centre, an art gallery, a rentable venue for events, and, of course, a café.

“Churches have become historical sites, tourist sites, and places to experience music, as much as somewhere to connect with a god”

I am very drawn to this repurposed church, and the question of what its secularisation suggests in regards to how we engage with church buildings in modern England. Renovated churches are popping up all over Cambridge. Pembroke College’s new auditorium is the converted Emmanuel United Reform Church, beautifully converted into a music rehearsal space and conference hall. I attended a poetry reading in the auditorium earlier this year, and sat amazed as Sean Hewitt’s lyrical voice reverberated throughout the room in a hauntingly sacred manner. The space, undoubtedly, affects the event – the vaulted ceilings echo the striking keys of pianos at musical events, while the stone closes, harsh and cold, around heated debates.

I was surprised to discover that Michaelhouse Café rents out several of its spaces for events, including its chapel and ‘Montefiore Room’, bringing to mind questions about the nature of this place. If you rent out the Chapel for £100 an hour, how does this setting affect your event? Can a sacred space truly become secular? It seems that they can, and they are. In general, these conversions reflect the increasingly secularised way in which people view churches. For my non-religious friends, churches have become historical sites, tourist sites, and places to experience music, as much as somewhere to connect with a god.

Although, this doesn’t answer the question of how the secularisation of church spaces serves our community. What is the driving need fuelling these conversions across Cambridge?

“In the cold, or the wet, community scatters back to its rooms and cafés – shut off, and charged for entry”

I believe that it is a vital one: the lack of third-party, non-commercial community spaces. In Cambridge, this issue is particularly relevant. Unlike at other universities, our SU doesn’t function as a neutral space to relax in, and most colleges are barred for entry without a college-specific CAMcard. Bars and coffee-shops depend upon buying food or drinks to stay, and, even then, are so busy that you feel guilty hogging a seat all day. Your room is your best bet for a free, calm place to sit and work all day, but is not a sociable community space. We are divided between colleges, divided between courses, divided from non-student Cambridge citizens, and as a community there are few places where we can gather together. Where is our third-party community centre? Is it the library in the New Arcade Shopping Mall, which most Cambridge students haven’t heard of, or Jesus Green and Christ’s Pieces, those open outdoor spaces where everyone is free to gather, to see the fireworks on Bonfire Night, or lie in the sun? Where do people of all backgrounds come together for free, to talk, to sit, to work, to celebrate? In the cold, or the wet, community scatters back to its rooms and cafés – shut off, and charged for entry.

In the face of this, I ask: does the secularisation of church buildings represent the natural progression for structures that were always intended to be English community centres, but now exist within societies which are no longer predominantly Christian? If so, what does this secularisation achieve?

In the 19th century, the Christian Church built parish halls and community centres in order to discourage people from spending their leisure time at public houses. Sacrilegious events – trading, drinking, bargaining, were held in these ‘church house (s)’ while other, less controversial secular events, such as education, will-readings, festivals, dances, and plays, were hosted inside the church building itself. Furthermore, the BBC reports that, in the Middle Ages, over 1,200 religious sites in England and Wales designated themselves as ‘hospitals’ for the sick and injured.

“The history of churches is speckled with the evidence of community at its heart”

The history of churches is speckled with the evidence of community at its heart. It is a legacy acknowledged in the government’s 2017 ‘Taylor Review’, in which they argued for the maintenance of churches on the basis of their position as “places of celebration, culture, commemoration and community gatherings, places of sanctuary and worship, and a resource for people of all faiths and none.” The government thus asserts the centrality of churches as a place for community beyond their religious purpose.

The secularisation of St Michael’s into Michaelhouse Café is not in conflict with its other religious endeavours. Churches have always been gathering spaces, and now, in a multifaith society, the secularisation of one or two of them in a town with dozens might go a long way to rekindle that community gathering space. This purpose is now fulfilled by Michaelhouse Café, who manage to balance their religious dedication to their Christian community with a space to house art, events, and tea. Although, in an ideal world, their space would be free to sit in, they do declare on their website that they provide concessions on renting rooms for community events – a small ideological victory.

Churches do not have a duty to become third-party, secular spaces, nor does one have to feel comfortable or neutral about a church being made into one. But sitting in Michaelhouse Café, or Pembroke’s new auditorium – places of education and meeting points for the elderly – I can’t help reflecting that in some small, perhaps insignificant way, these ancient stone buildings have found their way home.