Lonely this Christmas: the holiday season in campus novels

Feeling nostalgic, Felix Armstrong examines the Christmas term in books and film, a time of anticipation and uncertainty

Last week I, along with the rest of grey and snowless Cambridge, watched Instagram stories in bitter jealousy as my friend from the Other Place captured snowflakes falling in a perfect flurry around the Radcliffe Camera. Once the envy had subsided, I was struck by the simultaneous warmth and cold which has always enchanted me in literary depictions of the Christmas term. While I didn’t grow up idolising Oxbridge (partly in protest to being left out of a Year Seven trip to Oxford), campus novels — books set in universities or colleges — have formed an integral part of my literary taste, and their depictions of the weeks leading up to the holidays are particularly charged with the cosy charm which this genre majors on.

“As the Christmas term draws on, a hope of escape begins to flicker in the distance”

Christmas in campus novels is an oxymoron. This genre is so popular because of the closed, high-pressure setting it offers an author, forcing questioning, angsty teenagers to come to terms with their identities inside a suffocating, though often idyllic, microcosm. As the Christmas term draws on, a hope of escape begins to flicker in the distance. The term becomes a waiting game, as students plod on through the shortening days, refusing to nourish their growing belief that the campus isn’t the whole world after all, that Christmas might come to bring them home.

I remember being struck with this feeling during the long Michaelmas of my first year, during what must have been a heavy week five. Accompanied by a vivid mental image of a huge Christmas tree being put up in a grand dining hall, it took me days to place this feeling. It eventually came to me — Harry Potter. The books that I haven’t touched since I was eight? The films that I smugly remind my friends I have hardly watched? The franchise which has been soured by the online belligerence of its creator? Alas.

“With the Christmas season often comes the solidification of the literary found family”

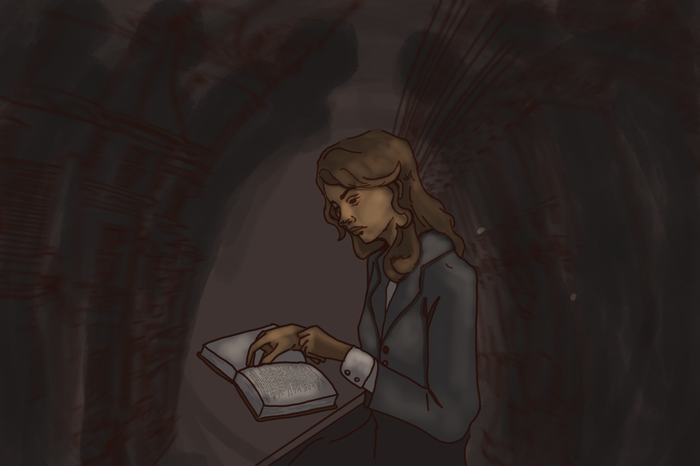

Though I had gone to great lengths to avoid Harry Potter throughout my childhood, its enchanting evocation of Christmas must have slipped through. Looking back at the first book, its blend of warring warmth and coldness, of hope and apprehension still stands: “No one could wait for the holidays to start. While the Gryffindor common room and the Great Hall had roaring fires, the drafty corridors had become icy and a bitter wind rattled the windows in the classrooms.”

With the Christmas season often comes the solidification of the literary found family, and nowhere is this more prevalent than at Hogwarts. Ron’s selflessness in giving up his cosy family Christmas celebrations in order to keep Harry company, whose tumultuous home life means a return for the holidays is less than desirable, provides a sweetly juvenile warmth against the backdrop of the harsh Scottish winter. For Harry and co., Christmas in the campus novel is not so much of an oxymoron after all.

The most interesting passages of Donna Tartt’s The Secret History come during this period in term. Richard Papen, a working-class student, obscures his real identity to fit in with the enchanting aristocrats that make up his Classics class at an exclusive liberal arts college. When they vanish upstate for the holidays, Richard is left behind, kicked out of his dorm and onto the street. But even Tartt gives in to the spirit of the holidays, when Henry turns up out of the blue to save Richard from near death. Tartt deftly manipulates the found family trope, though, as it turns out that Henry exploits Richard’s wintry loneliness to keep him in his debt.

“Serene snowy scenes are often paired with Britain’s elite universities in popular culture”

Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers is a love letter to being left behind. Though a campus film rather than a novel, this recent gem extracts Christmassy tenderness and charm from the found family trope. After Angus Tully realises too late that his mother isn’t whisking him off from boarding school for a ski holiday after all, he builds a makeshift family Christmas with his oddball Classics teacher and the school’s grief-stricken cook, set against a snow-white New England backdrop.

Serene snowy scenes are often paired with Britain’s elite universities in popular culture. As happened earlier this month, our social media feeds are washed with white-dusted spires every time Oxbridge is visited by snow. This time, it was a video of a pair of foxes playing in the gothic, snow-filled quad of Magdalen College that went viral. Last week, satirist Jonathan Coe visited Heffers to promote his new Cambridge-set novel The Proof of My Innocence, the timing of which was no doubt motivated by the strong tie between Christmas and campus novels.

In literature, the otherworldliness of the holiday period amplifies the dislocation felt by these characters. As a silence descends and the green turns to white, these strange, often elite settings become even more alien. The privilege and history of these fictional institutions are a reflection of how our culture fetishises real-world ones. Does combining this allure with the cosiness of a Christmas scene make these spaces feel more attainable, or does it merely enhance a fantasy?

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025

News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025 News / Cambridge researchers build tool to predict cancer treatment success19 April 2025

News / Cambridge researchers build tool to predict cancer treatment success19 April 2025 News / Cambridge researchers find ‘strongest evidence yet’ of life on distant exoplanet18 April 2025

News / Cambridge researchers find ‘strongest evidence yet’ of life on distant exoplanet18 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025