Small Things Like These: difficult questions, no easy answers

Claire Keegan’s novel, and its recent film adaptation, asks whether small acts of rebellion are worth making, writes Heather Leigh

Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is perfectly titled: the novel speaks to the helplessness we feel when faced with the vast and systemic injustices of our society, while exploring the difficulty and complexity of our small acts of rebellion. Are these acts insufficient or necessary, or perhaps both? At just over 100 pages, the book itself is a small thing. Keegan’s creation is painfully beautiful and beautifully painful. Every word is steeped with meaning and lyricism, and though the contents of the book refuse to decide for the reader whether these small acts are enough, its form at least bears testament to the potency of the minuscule.

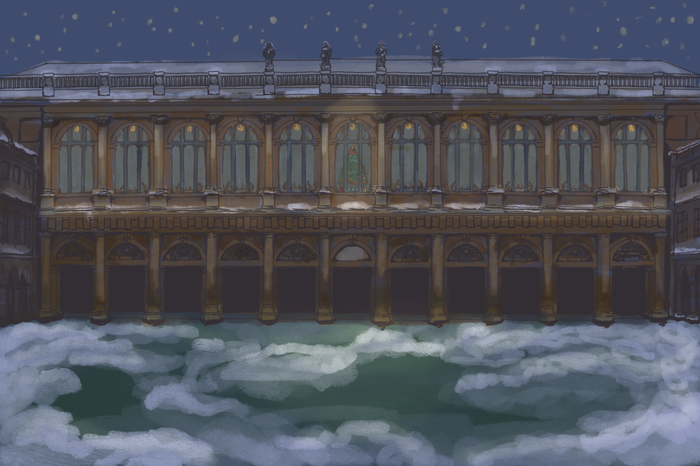

In 2022, Small Things Like These won the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the Rathbones Folio Prize. It’s easy to see why. Set in Ireland in the Christmas of 1985, the novel focuses on Bill Furlong, a coal merchant who finds a girl locked in the coal house of the local convent, which governs a Magdalene laundry. Magdalene laundries were set up for women who violated religious codes — such as prostitutes or those who had children out of wedlock — and ran from the 18th to the late 20th century. The last laundry was shut down less than 30 years ago. As Keegan explains in her note on the text, around 30,000 women were “concealed, incarcerated and forced to labour in these institutions,” which were “run and financed by the Catholic Church in concert with the Irish state”. The central tension of the text is whether Bill will surrender the girl back to the laundry or take a stand against the unspeakable cruelty that is being inflicted there.

“The novel grapples with the fine line between self-sacrifice and self-destruction”

The nuns who rule over the laundry also run the local school which Bill’s five daughters all hope to one day attend — the convent controls every aspect of society. If he chooses to protest against the laundry, Bill risks alienating his family from the parish community and from their sole access to education. In an interview with fellow Irish writer Colm Tóibín, Keegan notes that part of the irony, painfulness, and absurdity of this novel is that it revolves around a Christian man who struggles to practise the love and charity of his faith in a village dominated by the Catholic Church. “It would be the easiest thing in the world to lose everything,” thinks Bill. But then again: “was there any point in being alive without helping one another?”

The novel deals with a very contemporary concern: that we cannot do anything to help those who need it most, or that what we can do is not enough. Small Things Like These grapples with the fine line between self-sacrifice and self-destruction. Keegan confronts the deeply uncomfortable reality that to ignore injustice is an easier and often safer option, while reaffirming the notion that inaction is a form of action. “To ignore evil is to become accomplice to it,” said Martin Luther King Jr: “society’s punishments are small compared to the wounds we inflict on our soul when we look the other way.” This, of course, is easier said than done.

Keegan’s novel has recently been adapted into a film, starring Cillian Murphy and directed by Tim Mielants. It is, like the book, exquisitely crafted. Watching the film, I was struck most by its quietness. Dialogue is minimal: the primary sounds are crows calling, church bells ringing, tap water running, people breathing. There are long scenes of Bill driving, walking, washing his hands clean of coal dust. The film is based upon images rather than conversation, much like the novel itself. “Early one morning, Furlong had seen a young schoolboy drinking the milk out of the cat’s bowl behind the priest’s house,” writes Keegan. She doesn’t need to preach about poverty – the image speaks for itself.

“The potency of Keegan’s work is that it doesn’t provide a straightforward message”

Bill’s desire to help others is influenced by his upbringing at the hands of Mrs Wilson, a wealthy widow who took him in after his unmarried mother conceived him aged 16. He is keenly aware that had it not been for Mrs Wilson’s “daily kindnesses,” “his mother might very well have wound up” in a Magdalene laundry herself. Mrs Wilson’s small, everyday acts of compassion radically alter the course of Bill’s life, and yet — as his wife Eileen points out — “sitting in that big house with her pension and a farm of land […] Was she not one of the few women on this earth who could do as she pleased?”. “People could be good,” thinks Bill. The conditionality of the verb carries weight — are we supposed to believe that people can be good if they’re courageous enough to defy corrupt social norms, or that some people can afford to be good because they’re in a uniquely privileged position?

Juxtaposing seasonal festivities with endemic suffering, moving between past and present, and exploring the power and limitation of charity, Small Things Like These is distinctly Dickensian. However, readers are faced with a story more devastatingly realistic and unapologetically complicated than A Christmas Carol. The potency of Keegan’s work is that it doesn’t provide a straightforward message. We understand Bill’s compulsion to take a stance against injustice; we recognise Eileen’s need to conform for the safety of her family. Eileen is not demonised but neither is Bill glorified — he is called “foolish” rather than brave in the book’s final lines. The question remains: are small things like these big enough to make a difference? There is no easy answer, in life or in literature. The narrative teeters between hope and despair, closing with a liminality that haunts readers long after the final page.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025