Cambridge’s spaces still bear the past’s misogyny

Cambridge’s sexism can’t be resigned to the past, argues Johana Trejtnar

On the Thursday before International Women’s Day, I joined a group of women outside Great St. Mary’s Church on King’s Parade for the annual Reclaim the Night protest. As bystanders looked bewilderedly at the group of women standing together in the dark, representatives from Cambridge rape campaigns and women’s officers took turns speaking into a megaphone. They shared stories of the challenges female students face every day, both on the streets and within the University itself. The protest took place in the very spot where, 128 years ago, men hung the effigy of a female cyclist. Despite now being admitted and earning degrees, protests like Reclaim the Night are a stark reminder that Cambridge is still not the safe haven of learning for women that it has been for men for centuries.

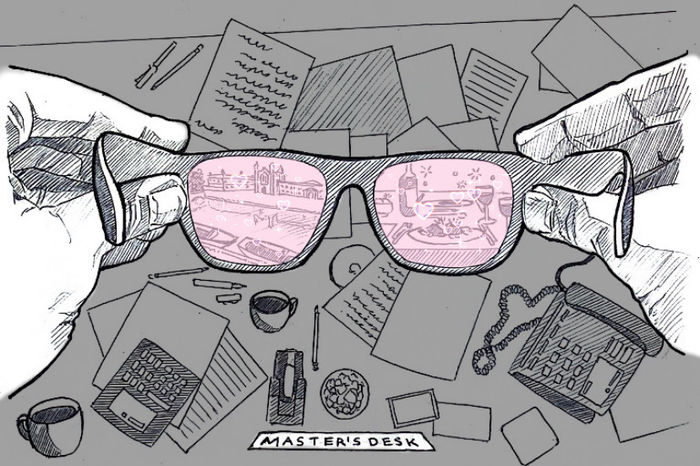

In celebration of International Women’s Day, the social media of various clubs and societies, as well as that of the University itself, became flooded with joyful messages about women’s contributions to Cambridge and hundreds of invitations to female-dominated panel discussions. A quick glance at Instagram in the days leading up to 8 March could give an uninvested observer the impression that Cambridge welcomes women with open arms – that the 739 years before women could obtain degrees have been neatly wrapped inside a Happy Women’s Day chocolate box and hurled into the depths of the Cam.

Upon a closer look, however, the edges of Cambridge’s pristinely marketed gender equality begin to fray.

“The protest took place in the very spot where, 128 years ago, men hung the effigy of a female cyclist”

Sexism is woven into the fabric of Cambridge’s history and its spaces. Not only were women barred from studying at the University, but until 1894, they could be arrested simply for walking its streets. In 1561, Cambridge was granted a special charter allowing it to imprison any woman “suspected of evil”. Fearing that local women might “corrupt” undergraduate men, the University used this law primarily against young working-class women found walking with undergraduates after dark. None were given a fair trial, nor was there any evidence of wrongdoing. Still, they were held in the University’s notoriously cold and damp private prison, sometimes for weeks at a time. One girl died after spending a night there. Beyond this, Cambridge had its own special police force – nicknamed “the Bulldogs” – to patrol the town, and “unruly” women were sometimes publicly whipped.

Although this special charter was eventually revoked and the first women’s college – the faraway Girton – was founded in 1869, misogyny did not disappear from Cambridge’s streets. In 1897, a vote on granting women degrees turned into a riot. Men took to the streets and hung a grotesque effigy of a female cyclist from what is now the University Press bookshop. The University rejected the proposal by a vote of 1,713 to 662.

“The fight for rights is rarely a straight line”

The last college to admit women, Magdalene, did so in 1988, an occasion met with mourning rather than celebration. Male students donned black armbands, flew the college flag at half-mast, and reportedly marched through Cambridge carrying a coffin, symbolizing what they saw as the imminent death of their college.

The history of women at Cambridge seems, on the surface, like a steady march toward progress. The University’s official section on women, titled “The Rising Tide,” ends with celebratory messages about female Nobel laureates and the incalculable contributions of Cambridge women. But, the fight for rights is rarely a straight line. A glance at the United States today suffices to prove how dangerous it is to assume that gender equality is final and irreversible. The reality present in these streets, far removed from official web pages, is far messier than an International Women’s Day Instagram post suggests.

At the Reclaim the Night March, the protesters spoke about feeling unsafe in Cambridge’s streets, recounting instances of colleges telling rape victims to “work it out” with their attackers and condemning the University for failing to address violence against women. While these issues remain unresolved, while articles about the gendered grade-attainment gap and a supervision system that disadvantages women continue to appear in Varsity, female students will never feel truly welcome at Cambridge. As long as women feel the need to organize these protests year after year, the University’s misogynistic past will continue to shape its present for non-male students.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a letter to letters@varsity.co.uk or by using this form.

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025

Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025

Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025