How not to respond to disclosures of rape: a practical guide

Our anonymous columnist returns to share common pitfalls when discussing rape, and the importance of simply listening

Content note: the following article contains discussion of rape

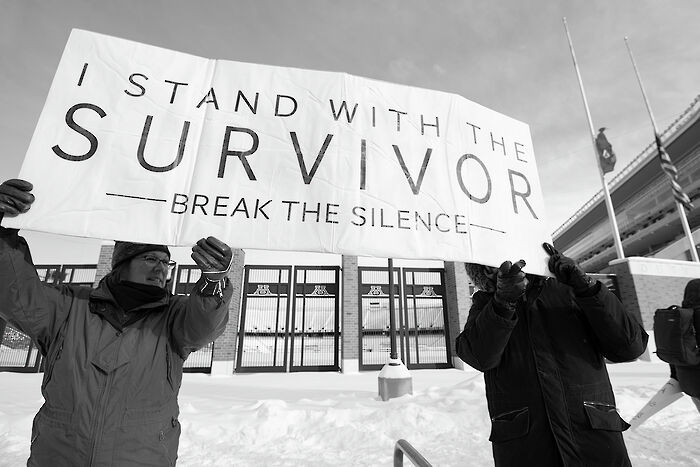

#MeToo has got us talking about rape and other forms of sexual assault and abuse more than ever before, but we’re still not a society that is good at listening. I am continually astounded by the array of unprofessional and inappropriate responses I receive when I tell people I’ve been raped.

Medical professionals, academic staff, friends – while many have listened sympathetically and with the best intentions at heart, the examples below are all real instances of ways people have responded to me telling them that I’ve been raped. These kinds of ‘bad’ responses catch me off guard, turning a conversation I am prepared and ready to have into a situation in which I am deeply uncomfortable. I do not mean to police what people should say or suggest what is best for all victims of sexual violence; however, I do believe the following to be useful general pointers, with some use in other kinds of difficult conversations, particularly about mental health.

I am continually astounded by the array of unprofessional and inappropriate responses I receive when I tell people I’ve been raped

1) Excessive shock or sympathy

Shock and sympathy are the most natural responses to a sudden disclosure of something traumatic or difficult. It is, of course, totally reasonable to respond in this way. However, as far as possible, avoid making your reaction over the top. Expressing a degree of shock and sympathy is to be expected (a gentle “I’m sorry to hear that” works well), but anything more exaggerated is likely only to make the speaker uncomfortable and feel guilty for upsetting you. Avoid putting them in a situation where they are having to comfort you. True story: one academic sat and repeated “Oh my goodness, I am shocked” until I had to tell them it was OK and move the conversation onto books. Staying calm almost always makes the conversation more pleasant for both parties.

2) Asking for detail

This is surprisingly common: responding to a disclosure of rape by pressing for further details. I think this often comes from a place of shock, of being taken aback by the information presented, and issuing a panicked question of reply. Questions can range from the somewhat benign (“have you had counselling?”) to the more problematic. Especially avoid questions asking why the speaker did not act differently: these very quickly stray into victim-blaming territory. Bear in mind that disclosing this kind of information is never easy, and the speaker will likely have told you all the detail they feel comfortable providing. Don’t press for further information, and keep the questions to a need-to-know basis. If you sense that the speaker wants to have a longer conversation and it is appropriate to do so, ask open, non-suggestive questions (e.g. “how are you feeling about that?”).

3) Making assumptions

Try to avoid making assumptions about the incident or the speaker’s feelings. These tend to project problematic assumptions about rape onto what is ultimately a very individual situation. In a society with certain preconceptions about rape, leading questions (“was it a stalker?”) perpetuate stereotypes about what sexual violence looks like, and are generally not useful. Steer away from presumptions about how the speaker is now feeling, or what facets of the situation may bother them most; again, this is a very personal experience, and it is important to give them personal space to process their own feelings. It is also important to try to mirror the speaker’s terminology: even if it sounds like rape to you, if they are using the term sexual assault, follow their lead. Personally, I’m not a fan of euphemism and prefer to directly refer to the incident as ‘when I was raped’ and ‘my rapist’; others may find those words upsetting.

4) Me too

Again, this is a very natural response, and, if employed carefully, can be appropriate. However, be mindful of the fact that it not always helpful to respond to a difficult disclosure by speaking about your own experience or that of other people you know. Solidarity in hearing of similar experiences can be a useful tool, but, especially in the early stages of recovery, I knew I needed to be self-centred. Hearing the stories of others was upsetting and unnecessarily triggering.

5) Praise

Another response that is well-intended but unfortunately often unhelpful. Responding by telling the speaker how ‘well’ they are doing, or how ‘brave’ they are again enforces ideas about how one ought to feel about being raped and can make the speaker feel a sense of victimhood more strongly. Personally, I find this can easily feel patronising, especially when I think the person giving out praise has no idea of how I am really doing.

Most important of all is to listen. Provide a gentle, calm and encouraging space for the speaker to share what they wish to share, in their own words, and you can’t go too far wrong.

Comment / London has a Cambridge problem 23 December 2024

Comment / London has a Cambridge problem 23 December 2024 News / Chinese students denied UK visas over forged Cambridge invitations22 December 2024

News / Chinese students denied UK visas over forged Cambridge invitations22 December 2024 Arts / What on earth is Cambridge culture?20 December 2024

Arts / What on earth is Cambridge culture?20 December 2024 News / Cambridge ranked the worst UK university at providing support for disabled students21 December 2024

News / Cambridge ranked the worst UK university at providing support for disabled students21 December 2024 News / Cam Kong? Ape-like beast terrorises student24 December 2024

News / Cam Kong? Ape-like beast terrorises student24 December 2024