Ending my love affair with nicotine

The romanticisation of smoking seems ever-present. Ella Hawes shares how she has combatted her addiction during the pandemic

Content note: this article includes detailed discussions of addiction

I quit smoking during the pandemic. It took more than a year of watching news footage of hospital respirators and peer pressure on a global scale to finally (finally!) kick the habit. It wasn’t idiocy, or delusion, or enjoyment that kept me smoking for almost a decade — just plain, old addiction.

I can remember the very first puff I took: I was a scrawny, awkward teenager stumbling into a friend’s back garden, stolen bottles of spirits in our hands, somehow pretending that the coughed-out smoke made us cooler. And I remember that very last one: alone, the last one of my housemates to cave under the weight of the pandemic, on a crisp Dublin morning.

“Smoking became synonymous with a lifestyle of free abandon and no tomorrows”

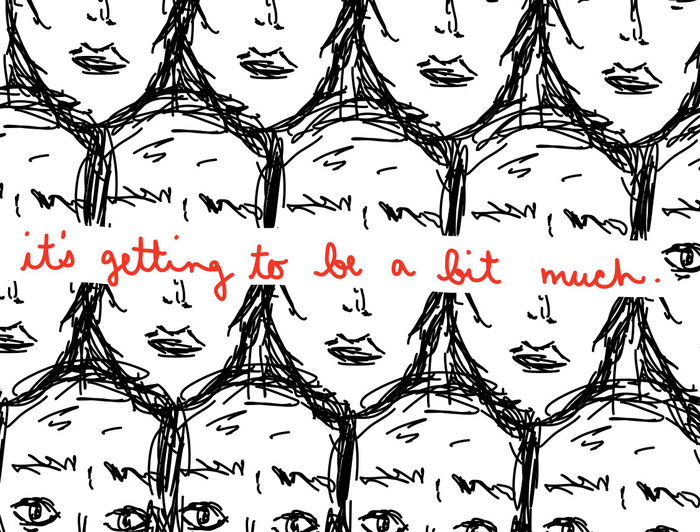

There were thousands in between that my body felt but my mind barely even registered. Chain-smoking in bedrooms cloudy with fumes and guitar music; cigs on the way to trains and buses and planes, anxious about the enclosed, nicotine-free spaces ahead; rollies cobbled together from old butts in the early hours after the nightclub, when shop owners were still asleep. Solo, contemplative cigarettes, quick work-break smokes, best-friends-for-the-night smoking area conversations.

For me, smoking became synonymous with a lifestyle of free abandon and no tomorrows. I leaned in urgently to the stereotype of the wayward, adventuring free spirit that movies and music idolised, fully embracing the sex, drugs and rock-and-roll living that promised so much but said so little.

Throughout my early twenties, practically everyone I met smoked. Partly, that’s to be expected: if you’re catching some “fresh” air outside the warehouse party at 4 AM, those briefly deep and beautiful friendships will be constructed around the ring of your cigarette-clutching hands. I spent a long time travelling and everyone smokes on the road. You don’t think about things like health or consequences when the driving force of your actions is freedom. But most people go home at some point, and I didn’t.

Years passed and it felt like I would never quit. Even when my morning ritual of a coffee and cigarette meant shivering in the Hungarian winter, breathing out smoke which froze as it hit the air. Even though I would get a cough every single year which kept me awake all night with the bed frame shaking, lying to myself about needing to see a doctor. Even when both my parents started smoking again after decades because their kids did it now, and I pretended to myself that I wasn’t responsible, that I didn’t feel guilty.

“I began to realise that consequences and tomorrows can be a good thing”

Of course, there were good bits, too. It was easy to feel little moments of humanity — all you needed was to lend someone a lighter and they were your mate, at least temporarily. You could have a perfect friendship for the time it took to burn down to the filter and then walk out of each other’s lives. In a world in which you’re far more likely to have a genuine connection with someone online than face-to-face with a stranger, those moments can feel special. There is an instant bond when you’re united in the self-imposed exclusion of a smoking area.

Sadly, I started to grow out of the carpe-diem-at-all-costs frame of mind. Raving started to lose its magnetic pull for me and even travelling became unfulfilling. I began to realise that consequences and tomorrows can be a good thing.

As my reckless spontaneity softened, I started to drink less, party less, stay in the same place for more than a few weeks, and the desire to smoke seemed more and more absurd. The realisation that this habit was killing me, and it wasn’t cool or edgy or revolutionary became painfully clear. Not to mention, there was a respiratory virus governing our planet for a while, and it felt a little silly to make its conquest even easier.

It’s hard to know why so many people (around 5 million in the UK) still smoke these days. There is a vague sense that smoking is anti-establishment. It really isn’t — UK smoking tax revenue brings in an estimated £8.7 billion for the government, around four times the cost the NHS shoulders for smoking-related healthcare. The media representation of smoking as aspirational has been dying out for years. Yet there is a residual — and oddly pervasive — belief that smoking relieves stress, when really it only causes anxious withdrawal to become a constant aspect of your life, and this stress alone is soothed by a cigarette.

The only real reason to carry on is addiction, and along with all other addictions, its users should be respectfully and non-judgementally helped to stop.

After quitting, I started being able to breathe again. Not just physically (I took up running and did my first half marathon within a year of stopping smoking), but also mentally. I’d always thought I had no willpower and that a lack of success would be inevitable for me, because if I couldn’t give up this one habit, how could I have the inner strength for anything?

But knowing that my very last addiction had been conquered, I started to believe in myself again.

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025 Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025

Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025 Lifestyle / First year, take two: returning after intermission14 April 2025

Lifestyle / First year, take two: returning after intermission14 April 2025 Sport / Cambridge celebrate clean sweep at Boat Race 202514 April 2025

Sport / Cambridge celebrate clean sweep at Boat Race 202514 April 2025