Zoetrope: the existential crises of Winnie-the-Pooh’s Russian cousin

Presenting a fascinating comparison of Disney and Milne to Russian animation, Ian Wang‘s latest column touches on some much needed sincerity in the realm of children’s cinema

For children all over the world, Winnie-the-Pooh is one of the most beloved and instantly recognisable characters ever created. Through countless theatrical shorts, TV specials, and branded merchandising, we have all grown familiar with the image of the dopey, plump, honey-yellow bear called Winnie and his raggedy band of woodland friends.

“His eyes widen, the corners of his mouth curve upwards, he looks wistfully up at the sky, as if in thanks to God”

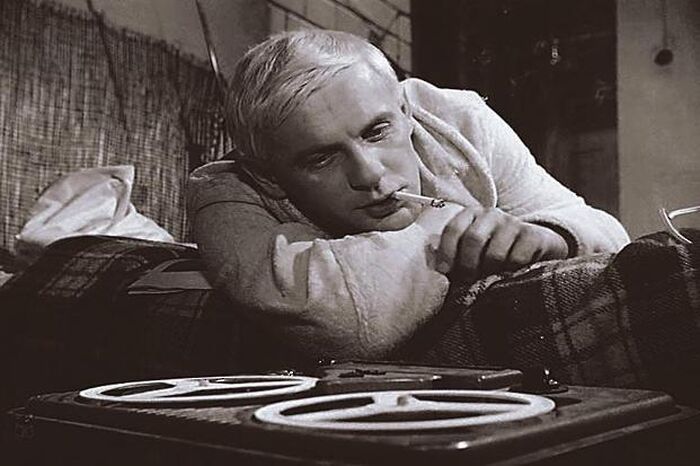

If one asks a Russian child to draw a picture of Winnie, however, they might conjure up something very different. While the various Disney adaptations of A.A. Milne’s original Winnie books remain the most popular worldwide, in Russia the classic Winnie adaptation is a series of shorts by venerated Soviet animator Fyodor Khitruk. These were released around the same time that Disney began putting out their series of Winnie shorts in the 1960s, and they put a very different spin on some familiar tales.

In contrast to the loveable, teddy bear-esque American Winnie, Khitruk’s Winnie looks more like, well, an actual bear. His fur is a dense, dark brown, his eyes sunken and vacant, he has pointy black claws, and almost never smiles. He speaks in a rapid, monotone voice, which generally varies between either a hoarse, introspective whisper or a raucous shout. His songs, far from serene, melodic showtunes like ‘Everything is Honey’, are more like hyperactive military marches, sometimes consisting mainly of onomatopoeic nonsense sounds.

Despite these very different aesthetic sensibilities, the films are extremely faithful to the original texts. All three Khitruk Winnie films are based on the first few chapters of Milne’s original 1926 story collection, with several lines lifted verbatim from the Boris Zakhoder’s Russian translations. Khitruk was motivated, first and foremost, by a profound love of Milne’s writing, saying in a 2005 interview that he was actually nervous about making his films because “every page of the book was so dear to me”.

Nevertheless, it is the small changes and inflections Khitruk does choose to implement that make his adaptations so special. Whereas Milne’s original books were inspired by his son, Christopher Robin Milne, and his relationship with his stuffed toys, Khitruk removes this framework completely. Instead, Khitruk’s Hundred-Acre Wood is a much more fantastical space, ungrounded by the staid confines of reality, trading Milne’s plain, British forests for wild, kaleidoscopic, otherworldly landscapes.

“As an adult viewer, I find these little diversions fascinating, and a little bit touching”

Although the childlike whimsy of Milne’s books still carries through, Khitruk injects a sense of world-weary irony and bleakness into some of those original lines. There is a moment in the first film where Winnie hears bees buzzing from a large oak tree, and gradually trails off into a tangent asking why bees even exist in the first place. In any other version, this might be played off as an example of Winnie’s charming absentmindedness, but the blank-faced, startled delivery of Khitruk’s Winnie, with his head in his paws, makes it seem like a miniature existential crisis.

This disorienting seriousness appears intermittently throughout all three of Khitruk’s Winnie films, perhaps most obviously with Eeyore. Whereas his persistent gloominess is easy to laugh at in the playfulness and silliness of the Disney adaptations, in Khitruk each cynical, self-deprecating statement stings that much more. There is a heart-breaking moment in the third film when Eeyore is brought a balloon by Piglet. Having received no presents on his birthday, on top of finding out he has lost his tail, he is in a sour mood, but when he learns of Piglet’s gift he slowly but surely perks up; his eyes widen, the corners of his mouth curve upwards, he looks wistfully up at the sky, as if in thanks to God.

And then the crushing blow: Piglet accidentally fell on the balloon on the way there, and it burst. Music cuts out. Close-up on Eeyore’s face as it slowly, pitifully sags from delight back into despair. He falls back, holding the limp balloon in one hand while Piglet turns the other way, weeping, unable to look him in the eye.

Ultimately, Khitruk’s films are still intended for children, and these few self-serious, self-aware moments are sandwiched in the kind of slapstick humour and linguistic playfulness one might find in any Disney adaptation of the books. But as an adult viewer, I find these little diversions fascinating, and a little bit touching. For so many of these old children’s books, they feel like they are set in stone, like their stories have already been understood and there is not any other way to interpret them. To see an adaptation as unusual and surprising as Khitruk’s, then, is incredibly refreshing, and I am glad it has endured for as long as its American counterpart

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025

Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025