Obsession, cinema and ‘Ferret’: an interview with Mojola Akinyemi

As part of her new column Lights, Cam-era, Action!, Katie Chambers sits down with Mojola Akinyemi to discuss her latest work, her role as a director and all things Cambridge film

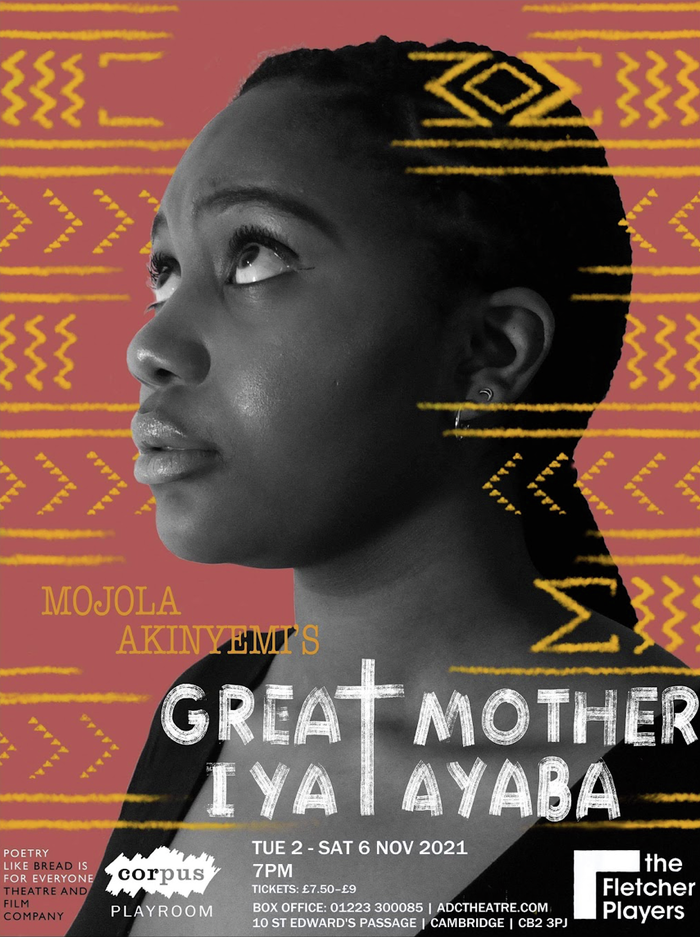

Mojola Akinyemi, an English finalist at Jesus, is a writer and director for films and plays in Cambridge. After a long hiatus, Ferret, her latest film, is finally in editing, in preparation for its first screenings and upcoming film festivals. Mojola wrote the screenplay in October 2020, but wasn’t able to start filming until November 2021 due to Covid restrictions.

"Ferret is about obsession,” Mojola summarises. Reflecting excitedly on films like Heathers (1988), Gone Girl (2014) and The Favourite (2018), Mojola tells me how it’s from these films that the inspiration for Ferret was born. There’s something about “wanting to be the object of desire, and the willingness to do anything to be it” that Mojola finds “really effective.” She’s particularly interested in exploring this trait in female protagonists. Like the women in these films, the women in Ferret go to extreme, unsettling lengths to get what they want, but we “root for them” even as we are shocked by their behaviour. Mojola is particularly fascinated by this effect at work in Gone Girl’s Amy Dunn, one of Hollywood’s most violent anti-heroines: “she is narcissistic, manipulative, but entirely justified in what she does.” When a film makes you painfully aware of an oppressive patriarchal superstructure, we agree, viewers can find themselves forgiving the individual female characters of even the most cardinal of interpersonal crimes. We talk about this effect at work in a group of films that is becoming known as the #goodforher canon (Mojola recommends Us (2019), Knives Out (2019) and The Invisible Man (2020).

“Viewers can find themselves forgiving the individual female characters of even the most cardinal of interpersonal crimes”

Another thing all these films have in common is that they are — even in all their darkness — very funny; indeed, Mojola classifies Ferret as “a black comedy.” When I ask about the comic element to this obsession narrative, she tells me that it is not only an effective tool to exacerbate even the most horrible of moments, but a directorial skill she really admires. “It’s easy to make someone scared or upset,” she says, “but it’s much harder to make them laugh.”

Ferret is far from Mojola’s first foray as either a director, writer or filmmaker. Her CV of work in Cambridge alone is remarkable, so I’m surprised when she says that she didn’t know she wanted to be a filmmaker until she got to Cambridge. The penny started to drop when she did some corporate work experience: “I hated it!” she laughs. “I don’t think I’m very suited to an office job. I don’t think I could ever feel fulfilled. I really like having something I can see that I’ve created. Being able to construct something, and having something that you can show people.”

Mojola identifies a talk in her very first term at Cambridge as a major turning point. “It was James McCarthy, speaking about how he became a screenwriter. He made it sound so doable. Before when I’d say I wanted to go into film people would say ‘Okay, good luck,’ but he really broke it down. I spoke to him afterwards, and he said I should write a screenplay. I was like ‘Oh my god.’ So I wrote something.”

When I ask her what her first screenplay was like, Mojola’s more than happy to admit that she doesn’t think it was very good. “I’m 20 years old! Some of the stuff I make is going to be bad. But if you’re scared of doing something badly, you won’t do anything at all.”

“[Being a director] is about being a born leader, about having a vision [that makes] people want to work with you”

Two years later, Mojola has worked with Watersprite, completed a course at the British Film Academy, and won the 2021 Other Brother Studio’s Film Fund, which is helping to fund Ferret. She’s keen to share the volume and quality of filmmaking opportunities available at Cambridge: “It’s so exciting that film in Cambridge is becoming more established, so there will definitely be people who want to help you make something.” Filming Ferret was an enormous team effort, including “eight actors and maybe twenty-five extras.” I’m intrigued by how Mojola approaches taking charge of so many of her peers. She recalls a scene filmed in the Maypole where thirty of her friends fell silent to listen to her direction. “It was terrifying! I started short-circuiting and told everyone to keep talking. I’ve never had that level of authority before.” She’s passionate about combating the idea that “to be a proper director you have to be loud and aggressive. It’s about being a born leader, and about having a vision [that makes] people want to work with you to create it.”

This synthesis of leadership and teamwork is important, Mojola explains, in a filming process that is complex and, at times, stressful. Not only is it reliant on (sometimes temperamental) technical equipment, but “you’re filming completely out of sequence, depending on location and people’s availability. The first scene of Ferret we [shot] is three quarters of the way through the film!” She goes on to talk about the difficulties filming in Cambridge posed: “[sometimes people don’t] want direct references to [the place] in the film.” But she finds positives in setting the film in the city. After all, she says, “that’s kind of the point: Ferret is a story that could be set anywhere.”

“A screenplay is very liminal, it doesn’t mean anything unless it’s made into something”

Mojola’s full of advice for aspiring filmmakers in Cambridge, and the first thing she says is “If you’re stressed on filming day, it’ll all work out!” Her other advice is more pragmatic: “get involved with Watersprite.” For her, it proved an invaluable stepping stone. She then talks about more tangible ways to get involved with film, such as the CUFA — especially their Fresh2Film initiative — and the ‘Film at Jesus’ short film challenges.

“Write as much as you can [as well],” she continues, “stuff that you can make... something that’s feasible for you to create. It’s all well and good writing a Hollywood blockbuster, but who’s going to be able to see it? A screenplay is very liminal, it doesn’t mean anything unless it’s made into something.”

“Knowing how to write a screenplay in the right format is so easy to learn.” She recommends YouTube channels like StudioBinder and Masterclass: “Watch the hell out of those videos. Learning the language, like ‘pan’, ‘zoom’ and ‘tilt’, and learning things like the fact that one page of a screenplay equates to about a minute of screen time, will make it much easier to make a shot list, which is the next stage.”

“Watch lots and steal things. I have a folder on my phone entitled Things in Films I Like.” (She shows me an opening frame from Little Miss Sunshine and tells me it inspired an opening shot in Ferret.) She quotes T.S. Eliot: “Bad poets imitate, good ones steal.” Mojola’s final piece of advice is “Make stuff for a reason, stuff that speaks to you.”

The course Mojola followed with the British Film Academy can be found here: https://www.bfi.org.uk/bfi-film-academy-opportunities-young-creatives

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025

Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025

Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025