Unearthing Nick Drake’s time at Cambridge

The folk singer’s university days reveal there was more to him than a recluse and a Romantic

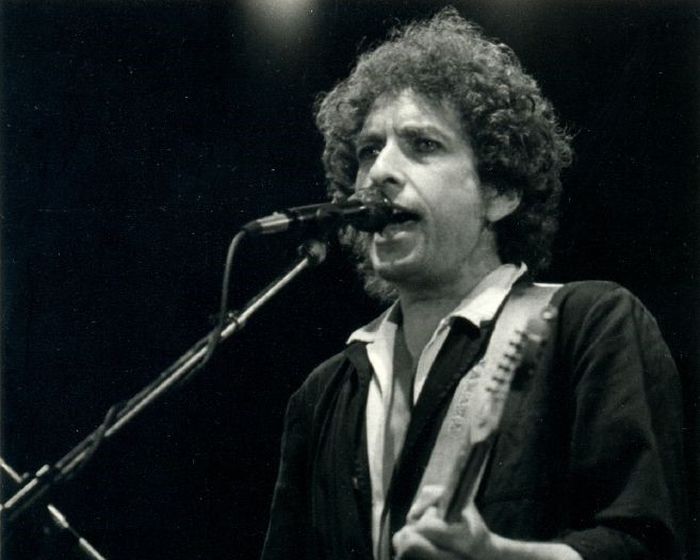

Leaning against a wall, one leg neatly crosses the other. His hair is almost covering his eyes, which refuse to look at the camera. Gazing at this infamous image of Nick Drake, he appears to be the impossibly effortless and the effortlessly cool. Only last year, a new covers album and a biography were released, showcasing the enduring legacy of an artist who continues to inspire musicians with his sparse folk music and dark lyrics. However, there is something this photo doesn’t immediately convey – something outside the popularised image of Drake as the recluse and the Romantic. His time at Cambridge, filled with humour as well as musical development, has become a footnote to his subsequent career and mental health struggles. Yet, it is worth exploring in its own right. Only then can we see more clearly the “river man” of his lyrics.

“Solitary study soon became increasingly secondary to the pursuit of his own art”

56 years ago, Nick Drake was finishing his first year at Cambridge. His study of literature, informed by not inconsiderable quantities of dope, would eventually influence the poetry of his lyrics, whether that be Wordsworth’s rivers or Blake’s poisoned trees. Solitary study, however, soon became increasingly secondary to the pursuit of his own art.

While most students were worrying about looming exams, Drake set his sights on a record deal with Island Records, the label that boasted the avant-garde and altogether unusual guitar practices of King Crimson. With this inspiration, Drake turned to experimentation with guitar tunings as a method of procrastination, hoping to find new harmonies that would make his songwriting stand out. However, Drake and his guitar would more often feature in his friends’ college dorms than any concert hall. And, for all Drake’s musical skill, not all his peers appreciated his dedication to the craft. One helpfully advised: “Drake, for God’s sake, put that bloody instrument away!”

Nevertheless, Drake tried to embrace a romanticised image of Cambridge and his peers often compared his figure to that of the poet Shelley: tall and thin but with an inner strength. For all his longing, Fitzwilliam in the 60s hardly provided an idyllic setting. Notoriously, the windows of its dorms rattled with passing traffic, leading students to plaster up their frames.

“Drake tried to embrace a romanticised image of Cambridge”

Most of Drake’s musical ambitions were realised outside his college. Caius was a hub for Cambridge’s folk scene and Drake performed at its May Ball in 1969. The event seems strange from a distance. It’s difficult to imagine the reserved Drake gently singing ‘’ Cello Song’ against a bustling backdrop of dancers dripping with jewels and feather boas. Still, it was not the strangest place Drake would perform. The American Cemetery on Madingley Road provided the venue for a three-hour session of song. Perhaps Drake’s understanding of mortality in songs like ‘Place to Be’ can be traced back to these moments between the gravestones.

Cambridge’s influence on Drake’s work can be heard most easily in the song ‘River Man’. Taking folk imagery and the character Betty Ford from Wordsworth’s The Idiot Boy, it offers a thoughtful view of the transience of any lived experience with images of “fallen leaves” and flowing water. More personally, his second-year accommodation across the river led him to cross Jesus Lock Footpath every day, where he perhaps noted the Cam’s ebbs and flows – a rhythm that could be replicated in song. Even behind this most romanticised image of Drake, however, we must remember that he also enjoyed chucking his friends into said river, granting a whole new meaning to what being a “river man” entails.

What should we think about Drake's time at Cambridge? Should we romanticise his revision diet of dope and Rimbaud, celebrate his fusion of music and literature, or ignore this period entirely and instead consider his influence on later artists like Kate Bush and The Cure. Clearly, this afterlife is significant. However, we must not forget the humour that pervades these stories from his Cambridge days – and which is just about visible in the half-smile he displays in those black-and-white photos we see of him today.

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025

Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s gossip culture is a double-edged sword7 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s gossip culture is a double-edged sword7 April 2025