Science in Art can help restitution of 100+ looted statues still in Cambridge, says Fitzwilliam Museum Exec

Varsity spoke to Dr Erma Hermens, Deputy Director of Conservation and Science at the Fitzwilliam Museum, about how scientific innovations can contribute to art conservation

Science and art: one cold, analytical, rational; the other warm, emotional, stirring. At least, that’s how they can seem, as though opposite ends of a very broad spectrum. But in fact, the two are fundamentally and inextricably linked – science underpins art while art informs science, in ways that can easily go unnoticed if you’re not looking.

Varsity spoke to the deputy director of the Conservation and Science division at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Professor Erma Hermens. She also is the director of the Hamilton Kerr Institute, dedicated to the conservation of easel paintings. The Fitzwilliam, Hamilton Kerr Institute, University Library and McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research collaborate in the Cambridge Heritage Science Hub (CHeriSH), a consortium that boosted collaboration in heritage science research in the University.

“It is important to realise that you can’t just send them back, you need to help”

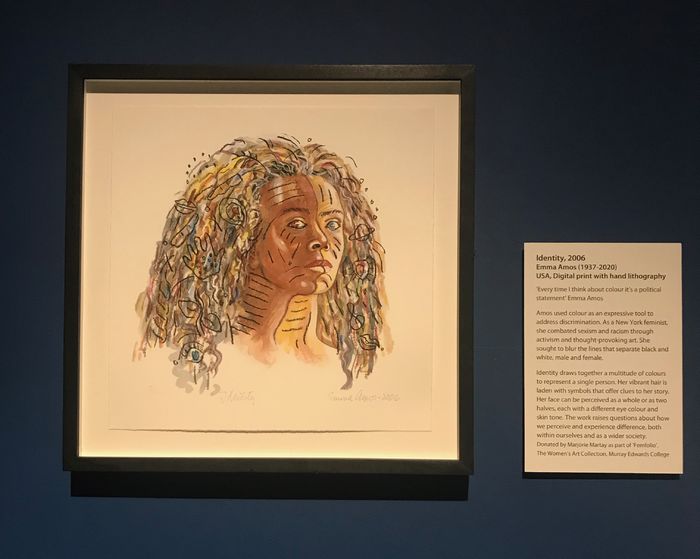

The Hamilton Kerr Institute also hosts two archives from 19th- to 20th-century colour manufacturers: C. Roberson & Co and Winsor & Newton. The Institute contributed materials from the archives, such as colour charts, pigments, and paint boxes, to the COLOUR: Art, Science and Power exhibition at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (ending on 23 April 2023), which explores our perceptions of colour in “exciting and unexpected ways”.

Science contributes to art conservation and research in many ways. Hermens pointed out some key techniques which have been long established. High-resolution photography using UV light indicate the presence of varnish, retouches, or specific pigments that “fluoresce” in different ways. X-Radiography allows the visualisation of internal structures, and along with IR photography, can indicate underpaintings, drawings or sketches which cannot be seen with the naked eye. Newer techniques offer even more detailed insight. Micro-X-ray fluorescence scanning of paintings, for example, sends a small beam of X-rays through a painting to generate elemental maps of, for example, lead, copper, and iron which correspond with pigments like lead white or iron-containing earth pigments like ochres. These methods of analysis can be used to unpick the painter’s studio practice, revealing often not visible details which might be missed otherwise.

In the last few decades, the arts and scientific fields have become more interconnected through technical art history, with scientists working closely with conservators and art historians combining a wide range of expertise. They collaboratively interpret data from scientific analysis, adding the story to the data, to paint as detailed a picture as possible when it comes to the composition and history of an artwork.

The Hamilton Kerr Institute is part of the CHeriSH consortium with the MAA, which continues to hold Benin Bronzes, sculptures taken by the British during the sacking of Benin City, Nigeria, in 1897. Hermens explained that the University “needs to look more into these processes of restitution, the safekeeping of these objects in Cambridge, and how we facilitate restitution” to native countries.

Focussed on engaging with new developments in science and approaches in conservation to understand the story and interpretation of artworks, Hermens explained how technical art history, where art historians are increasingly in dialogue with scientists, can help provide a unique insight into the history of artefacts in the museum’s collections – which in some cases, can also contribute to an understanding of the colonial history of artworks.

“Technical art history can contribue to an understanding of the colonial history of artworks”

Hermens remarks: “There is a whole ethics of conservation”. Cambridge museums continue to “engage in developments in science and new approaches in conservation”. They continue to “work on new methods” and maintain “dialogues with scientists” to support the research into and preservation of objects in their collections.

“Knowing about the physical make-up of an object through scientific analyses” can help understand the painting techniques of Rembrandt and other 17th-century Dutch painters, and to study degradation processes. The replacement of several traditional products with synthetic pigments in the 19th century is a particularly interesting period for technical art historians due to an increasing colour palette, the establishment of chemistry at universities and many changes in artistic practice.

Hermens gave an example of “smalt” – a blue pigment made from ground cobalt-containing glass, which tends to lose its colour when used in oil. Tracing the spread of the use of smalt, which seems to have originated in the Venetian glass industry and was exported all over Europe, but also to the Americas in the late 16th century by for example, the West India Company, as well as traded via the silk road to the East, adds a new perspective that “looks much more globally” to understand trade routes, the spread of material knowledge and artisanal practices of pigment making.

Technical art history also support decision-making on conservation treatment, as through imaging and analytical research we increasingly “know exactly what we are looking at’’. The Fitzwilliam Museum has recently applied a non-invasive imaging method which is most commonly used in the biomedical sciences to capture high-resolution images of biological tissue to ceramics and enamels. You might have been subjected to this technique, called Optical Coherence Tomography, yourself if you’ve ever had a picture taken of your retina by an ophthalmologist. If anything, these shared instruments highlight the degree to which scientific and art research methodologies can overlap.

There are also many opportunities to get involved with research at the Fitzwilliam and the Hamilton Kerr at various levels: as well as offering internships and a Master’s Programme in Easel Painting Conservation alongside internships, the Fitzwilliam also employs two junior research scientists and is recruiting a senior scientist, embracing these new developments and collaborations between art and science. Hermens also invites any one interested in collaboration, students and scholars, to get in touch.

This “engagement with all these new developments in science and new approaches in conservation” as also represented by CHeriSH, makes Cambridge a world leading environment for object and collection-based research and preservation of historic artefacts.

Hermens states how you can “look at an artistic object, have questions, conduct scientific analysis about the artistic process, learn more about the materials, and ask why the object was made in the first place, for whom, when, and, especially, how”. By engaging with new developments in heritage science and technical art history, as well as new approaches to conservation, the interdisciplinary team of researchers at the Fitz and Hamilton Kerr, can add texture and colour, to the material and historical biographies of artworks.

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025

Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025

Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025