The Revlon Girl review

This heartbreaking narrative is brought to the stage with subtle staging and deeply emotional performances – the result is both powerful and intensely moving

Drops of water fall from above the stage into a spotlight in the centre of an empty stage. Something rumbles but the audience are transfixed. And transfixed we will remain for the rest of the play, mesmerised by these characters: four women who have lost their children in the collapse of a spoil tip eight months earlier and the ‘Revlon girl’ who comes to give them a make-up demonstration. We are held by their tragedies and their comedies until we forget that what we are seeing is a preview, a before-the-action, a behind-the-scenes before the organised grieving begins. What we are waiting for, whatever that is, never comes. So we will make do with this.

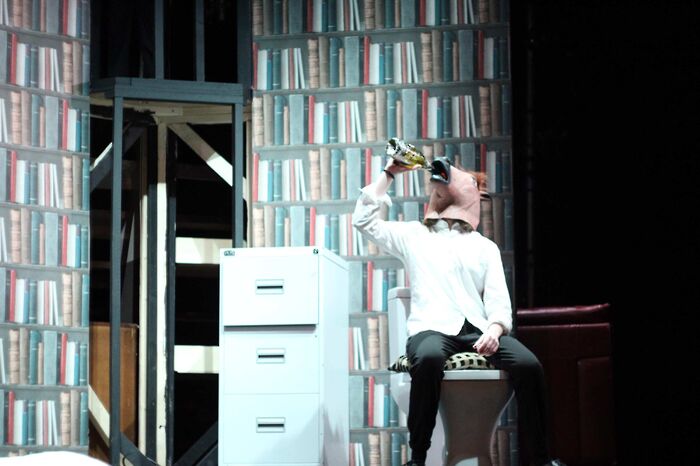

The characters construct the set themselves in the opening minutes, turning on the lights and creating from a blank space a semblance of structure in a table laid with make-up and two rows of chairs for the audience. They seem to forge their own stage and to set up their own expressive space in the worlds of both fiction and reality. A sense of self-sustaining runs through this play: as the inside space we see on stage becomes more animated, the outside world, fraught with the fear of judgment as it is, demarcated only by the Revlon girl’s flashy car parked at the front, seems to fade away, until the characters are standing in an echo chamber of their memories and feelings. The blankness of the scenery and the minimalism of the square, wooden furniture create a perfect silent point in the middle of this teetering village where disasters are waiting to happen – and where they have already happened.

The Revlon Girl (Emily Webster) is our route into this room: she is the only reason that we, the audience, can see these women and their grief, and she remains unnamed, on the other side of the room for almost the entire play. Webster wrings her hands and her responses to the scenes are self-consciously understated as she navigates the line between being deeply involved and yet so separate from what these women feel. Webster plays her part with just the right balance of brightness and helplessness, and the details of the changes in even the smallest of her movements load every moment with meaning.

Indeed Webster’s separation from the other women on the stage is just one example of how this production deals so effectively with space. Credit should go to Geraint Owen, Izzy Collie-Cousins and Lucas Marsden-Smedley for their direction here: space is made obvious, both in the larger sense of the stage, where the bucket in the middle is a constant reminder, intrusive and awkward and sometimes quite loud, of what is broken and can never be fixed, but also on the small scale of interactions between characters. For an hour, their only contact is when make-up is applied to their faces: when they do finally touch, it is a moment for drawing breath.

Each of the women in this play is wonderfully individualised. Freya Ingram (Sian) has a certain quiet efficiency-with-an-edge which reminds us that she is a young mother and not an old woman, and the depth of emotion which she reaches both in her own monologue and when listening to others is heart-breaking. Meg Coslett’s stream of consciousness as Rona is unafraid of expletives, scoffingly sarcastic and apparently thrilling with certainty or at least with anger – but she is utterly charming in her verbosity.

"The play rises and falls, pushing the characters together in their shared directionlessness only to pull them apart again”

Amelia Hills (Marilyn) plays the perfect watcher, acting even when she is not the centre of attention and yet able to erupt with such power before folding in on herself once more. Martha O’Neil as Jean is caught in the middle of this group, struggling to manage her feelings as a bereaved mother and mother-to-be and leaning on her faith as a way of getting through. These little people (it sounds better in a Welsh accent) become very big people on this stage: but big people acted with subtlety and a gentleness that cannot be over-praised.

The five women onstage manage the rhythms of this play with a precision that feels natural. There are moments of laughter which are executed with a genuine sense of relief which can only come from their complete emotional investment in the scenes they are acting and the stories they are telling, but these fragment all too quickly into bickering. The play rises and falls, pushing the characters together in their shared directionlessness only to pull them apart again. Ingram, Webster, O’Neil, Coslett and Hills carry out each motion with careful energy, giving the audience just enough hope in the laughing moments but forcing us to acknowledge but also understand the realism of their arguments when laughter gives way.

‘The Revlon Girl’ doesn’t offer answers or solutions. It doesn’t tell us that grief can be overcome and that everything will be alright. Because nothing ever can or will restore these mothers’ children to them. What it does tell us is that sometimes all you can do is exactly enough. This is a play full of things that can’t be said, but then are said too much, and then that we have to pretend were never said at all. Suddenly all speech has implications, and even the smallest filler words which the Revlon girl uses are a reminder of unimaginable pain. I came away from the Robinson Auditorium wondering how I could watch a play like this and just go straight home to write up a review as if nothing had happened. But what this play showed me is that things have happened – and we do go on.

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025 News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025

News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025 News / Cambridge University Press criticises Meta’s ‘dismaying’ use of copyrighted material28 March 2025

News / Cambridge University Press criticises Meta’s ‘dismaying’ use of copyrighted material28 March 2025 News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025

News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025 Sport / Light Blues prevail in thrilling Varsity encounter29 March 2025

Sport / Light Blues prevail in thrilling Varsity encounter29 March 2025