Salomé will leave you shaken

With the help of some stellar acting, this reimagining of Wilde has a lot to say about queerness

Salomé is a one-act play by Oscar Wilde. It tells the tale of the biblical-era Salomé, dancing seductively for her stepfather Herod in return for being brought the severed head of John the Baptist, who has rejected her advances and condemned her mother. It is a play of power, desire, and religion, and the script bubbles with a poetry and melodrama typical of Wilde. Eve Chandler’s adaptation takes the story to Weimar-era Berlin, the exploration of queerness woven into the story through the androgynous presentation of the titular character.

The production’s queering of Salomé was cleverly and subtly achieved. The character was continually referred to using a mix of he/him and she/her pronouns, undermining a fixed gender identity while bringing to mind the microaggressions of misgendering, though any sense of a ‘correct’ gender is obscured. Chandler evokes the fetishisation and objectification of this queer body powerfully through the long dance sections, a revealing costume, and staging that often positions the other characters as looking at Salomé from around the edge of the space, implicating and politicising the gaze of us as the audience. That said, the danger and precariousness of Salomé’s position, reliant on their sexuality and desirability to those (men) around them, was somewhat undermined by the casting of the female-presenting actors Sophia Orr and Enya Crowley in the evidently male roles of Patron and Doorman. Despite their best efforts, they came across as fairly nice and harmless, rather than predatory and libidinous, weakening the power of the opening scenes.

“The production’s queering of Salomé was cleverly and subtly achieved”

The presentation of John the Baptist also didn’t carry the punch it might have. The utilisation of the Corpus Playroom’s prominent stage door was clever, left open throughout the show to represent the entrance of John’s cell and creating a dark and ominous physical presence behind the onstage action. However, the choice to project Louis Davidson’s off-stage lines through a speaker again relied on an overstretched suspension of disbelief, as actors looked in one direction in response to a voice emanating from another, which undermined the power of the lines and the use of the space. Ironically, the microphone cut out a few times, letting us hear Davidson’s actual voice emanating clearly from the depths of the Playroom’s backstage, which was actually far more compelling.

The character also didn’t seem to have a place in the Weimar setting. Why would Herod, the cabaret-club owner, have a preacher in his basement? Why would there be a holy man, starkly dressed in white with a crucifix necklace, speaking in biblical prose and declaring moral judgements, in 1920s Berlin? This wasn’t the only thing weakening the sense of historical situatedness either; while the soundtrack was impressively made up of original songs, skilfully composed by Stan Hunt, it felt like a missed opportunity to draw from the rich tradition of cabaret music. In the end, the re-contextualisation came to be disappointingly cosmetic, the show being centred more around an ahistorical evocation of drag performance and queer identity than a particular engagement with the culture and politics of the period.

“I entreat people to come and see this production just to not miss out on these performances”

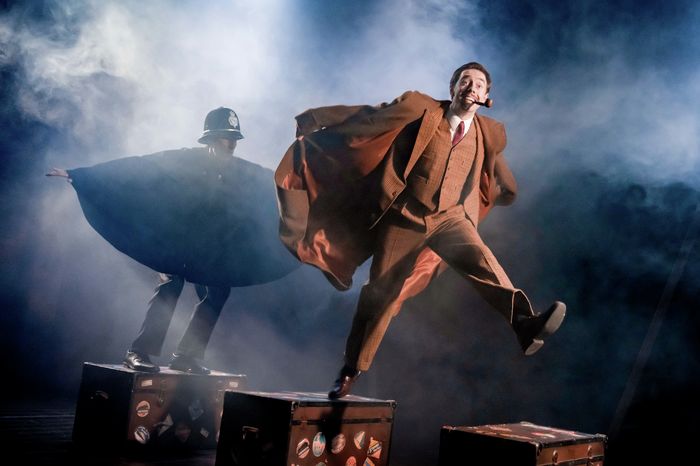

The show’s strength lies indisputably in its acting. Stand-out performances were given by Reuben Rackham and Toby Trusted as Herod and Salomé respectively. Rackham brought to the stage a playfulness and command of the space that was charming, charismatic, and incredibly enjoyable to watch. His characterisation was rich and varied, from the subtle play of power over those around him to the self-aware but totally infatuated desire for Salomé. Trusted was the total star of the show though. A long solo dance in the middle of a play is no mean feat, and they pulled it off with completely mesmerising commitment and flair. The dialogue was equally as strong, full of pathos, passion, and nuance. Wilde’s final image could easily come across as melodramatic and excessive, but in Trusted’s hands it was deeply powerful and disturbing. The show positively fizzed with energy and brilliance when these two capable actors played opposite each other. A highlight was the climactic scene in which Rackham traversed the stages of grief as Herod implores Salomé to change their mind, in counterpoint to Trusted’s tastefully understated repetitions of the fatal demand – ‘give me the head of Johnathan’. I entreat people to come and see this production just to not miss out on these performances.

As a show hoping to evoke the heady and anarchic Weimar era with its competing worlds of seedy nightlife and religious morality, Salomé doesn’t quite follow through. As a show setting out to explore queerness and Wilde’s viscerally powerful and beautiful script, it is a storming success, thanks in large part to brilliant performances from its lead actors. Ultimately, the latter of these leaves a far greater impression, and walking out of the Playroom I felt in equal parts moved and shaken by the power of what I’d just seen.

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025 News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025

News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025 News / Caius clock hand returned nearly 100 years after student prank31 March 2025

News / Caius clock hand returned nearly 100 years after student prank31 March 2025 News / Cambridge University Press criticises Meta’s ‘dismaying’ use of copyrighted material28 March 2025

News / Cambridge University Press criticises Meta’s ‘dismaying’ use of copyrighted material28 March 2025 News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025

News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025