Gender on stage: the art and challenge of casting Shakespeare

What can gender-swapped Shakespeare tell us about the limits in our understanding of gender?

The original gender-swapped casting in Shakespeare’s plays – which I am sure most of us heard about in GCSE English – occurred due to the poor perception of acting in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, which created a social stigma against female actors in public settings. Gender-swapped casting was therefore a choice born out of necessity.

Nowadays, however, the Royal Shakespeare Company also commonly gender-swap male roles with female actors for artistic and casting purposes. In their 2018 production of Romeo and Juliet, Mercutio is played by actress Charlotte Josephine. Deputy artistic director Erica Whyman said this representation of women on stage prevented feelings of alienation for audience members which could otherwise result from the predominantly male characters in Shakespeare’s plays.

But the practice of gender-swapping the actor playing the titular character of Othello is much less common than, say, that of Hamlet, for whom there has been a long tradition of the character being played by women. Roles such as Hamlet – who worries if he is ‘feminine’ and ‘weak’ in his failure to act on his revenge is a commonly (in fact, the most) gender-swapped character in all of Shakespeare; the long tradition harking back to Sarah Bernhardt’s portrayal of Hamlet in 1899.

“Why is it so hard to convince an audience member that an actor is momentarily a gender not their own?”

But a notable recent performance of Othello by a woman is Jessika D. Williams’s portrayal in the 2020 American Shakespeare Centre production. Just as the role would not have originally been played by a black man, so too would it not have been played by a woman. And yet in the same way that casting a black actor to play a black character brings out the nuances inaccessible for a white actor, similarly, a woman playing masculinity brings out nuances of Othello’s gender that a male actor might not notice, such as Othello’s detachment or guardedness as a method of power, which was keenly felt in Williams’s performance.

Othello is already a play about identity – Othello is a black man whose identity is in tension with the otherwise white Venetian world he occupies. He is referred to almost exclusively using slurs, envied, and rejected by his wife’s father because of his ethnicity. By choosing a female actor, the character’s themes of identity, and the idea of adapting oneself to fit the world around you, inevitably grow starker. Any woman who plays Othello, like the character himself, must adapt and shape her identity into a replicant of a male one. The fact that Othello isn’t fully accepted in Venetian society is made literal - the actor does not ‘fit’ the male identity of the character. However, this seems to reveal how, like actors on a stage, we might never truly be able to fulfil the identity laid out for us, just as Othello fails to fulfil the expectations laid out for him.

In the recent Pembroke Players production of Othello I watched – in which Othello (Lauren Akinluyi) and Brabantio (Helen Brookes) are both played by women - audience members were not absolved of their awareness that Othello was played by a woman; indeed, when leaving Pembroke Chapel, the first thing that I heard audience members discussing – as I half-expected – was the fact that women played male roles.

“The convention of gender-swapped casting demonstrates the shortcomings of our concept of gender”

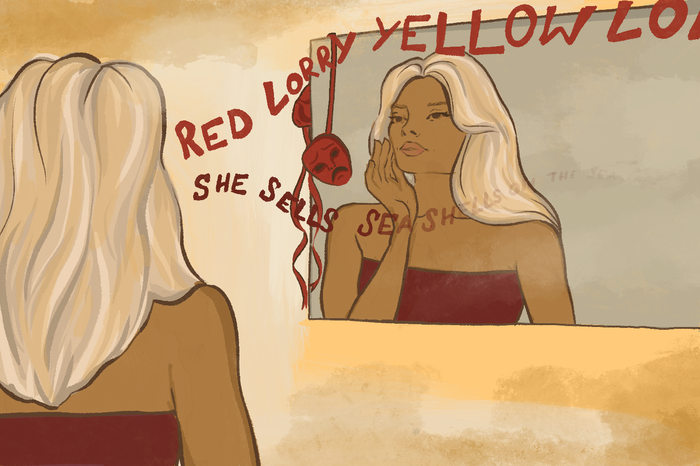

Does this mean that the actors failed to act another gender? I’m not sure. Rather, I believe this failure of the audience to be fully absorbed in the world of theatre perhaps reveals something about the unachievable nature of gender standards. The convention of gender-swapped casting demonstrates the shortcomings of our concept of gender and the retention of strict gender expectations. The question we should be asking: why is it so hard to convince an audience member that an actor is momentarily a gender not their own?

I think this is an important question to consider, as it reflects our own prejudices back to us. The theatre conventions of gender-swapping actors remind us of the unreality, the performativity, of gender barriers. Yet, our ongoing unconscious awareness of these gender expectations is stressed in how easily we feel them being traversed; how hyper-aware we are of gender.

In many ways, this hyper-awareness has broader implications for our awareness of gender in everyday life. If we are so focused on what does or does not constitute ‘correct’ gender performance, we may reveal inherent biases against gender non-conforming individuals, as well as more everyday expectations, such as the pressure on men to be tall and stoic or on women to remain wrinkle-free and shave their legs.

To put this shortly, gender-swapped theatre can pose a challenge to our strict concepts of gender; these performances ask us to focus on gender as something totally performative, and question our own willingness to accept that.

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025

Interviews / Meet the Chaplain who’s working to make Cambridge a university of sanctuary for refugees20 April 2025 News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025

News / News in brief: campaigning and drinking20 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s gossip culture is a double-edged sword7 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s gossip culture is a double-edged sword7 April 2025